CURRENT AFFAIRS – 24/04/2024

- CURRENT AFFAIRS – 24/04/2024

- Denying women child care leave is violation of Constitution

- Why High Court upheld Karnataka’s ban on hookah?

- Toss out the junk food, bring back the healthy food plate

- Towards a less poor and more equal country

- An overview of the PMAY-U scheme

- How is India planning to boost EV production?

- NABARD unveils strategy to mobilise green financing

CURRENT AFFAIRS – 24/04/2024

Denying women child care leave is violation of Constitution

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Indian Express

A woman, an assistant professor in a Government College in Nalagarh, approached the bench of Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud and J B Pardiwala with a plea.

- She asserted that the Himachal Pradesh government had denied her child care leave necessary for attending to her child suffering from a genetic condition.

Key Highlights

- Constitutional Entitlement to Women’s Participation:

- The bench emphasized that women’s participation in the workforce isn’t just a privilege but a constitutional entitlement safeguarded by Article 15 of the Constitution.

- It stressed the state’s responsibility as a model employer to address the unique concerns of women in the workforce.

- Importance of Child Care Leave:

- Child care leave serves a crucial constitutional objective, ensuring that women can maintain their participation in the workforce without being unduly burdened by childcare responsibilities.

- Without such provisions, women might be compelled to leave their jobs, undermining their right to work.

- Special Consideration for Mothers of Children with Special Needs:

- The court recognized the heightened challenges faced by mothers with children having special needs, citing the petitioner’s case as an example.

- It underscored the necessity for tailored policies to support such mothers, ensuring they aren’t disadvantaged due to caregiving responsibilities.

- Alignment with Constitutional Safeguards:

- While acknowledging the policy implications involved, the court asserted that state policies must align with constitutional safeguards.

- It emphasized the need for synchronicity between state policies and constitutional principles, particularly concerning the rights and needs of women in the workforce.

- Directive to the State of Himachal Pradesh:

- The court directed the state of Himachal Pradesh to thoroughly consider the grant of child care leave to mothers, including crafting specific provisions consistent with the Right to Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act for mothers of children with special needs.

- This directive aims to ensure equitable treatment and support for working mothers facing unique challenges.

- Constitution of Committee by the Court:

- The Supreme Court has also instructed to establish a committee to thoroughly examine all aspects of the matter at hand.

- Background of the Woman’s Case:

- The petitioner, an assistant professor, sought child care leave from the state government due to her son’s rare genetic disorder, Osteogenesis Imperfecta, which necessitated multiple surgeries.

- After exhausting her sanctioned leave, her further leave request was denied by the state, citing non-adoption of Rule 43-C of the Central Civil Services (Leave) Rules, 1972.

- Legal Proceedings:

- After the High Court dismissed her plea in April 2021, citing the state’s non-adoption of Rule 43(C), the woman appealed to the Supreme Court.

- She argued that the selective adoption of rules by the state contradicts the principles of a welfare state, the Constitution, and India’s obligations under international conventions on women and child rights.

About the Right to Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act

- The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act, 2016 is a landmark legislation in India that aims to uphold the dignity of every Person with Disability (PwD) and ensure their full participation and inclusion in society.

- It replaces the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995, and fulfills India’s obligations to the United National Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

- Key features of the RPWD Act, 2016 include:

- Definition of Disability:

- The Act defines disability based on an evolving and dynamic concept, covering 21 types of disabilities, including physical, mental, intellectual, and sensory impairments.

- Accessibility:

- The Act emphasizes the need for accessibility in public buildings, transportation, and information and communication technology to ensure equal participation of PwDs in society.

- Education:

- The Act mandates free and compulsory education for children with benchmark disabilities between the ages of 6 and 18 years, and inclusive education in government-funded and recognized institutions.

- Employment:

- The Act provides for reservation in government jobs and educational institutions, and additional benefits for persons with benchmark disabilities and those with high support needs.

- Guardianship:

- The Act introduces joint decision-making between the guardian and the person with disabilities in matters of guardianship.

- Advisory Bodies:

- The Act establishes Central and State Advisory Boards on Disability to serve as apex policy-making bodies at the national and state levels.

- Monitoring and Grievance Redressal:

- The Act strengthens the offices of the Chief Commissioner of Persons with Disabilities and State Commissioners of Disabilities, which will act as regulatory bodies and grievance redressal agencies, and monitor the implementation of the Act.

- Penalties:

- The Act provides for penalties for offenses committed against persons with disabilities and violation of the provisions of the new law.

- Special Courts:

- The Act designates special courts in each district to handle cases concerning violation of the rights of PwDs.

- Definition of Disability:

Why High Court upheld Karnataka’s ban on hookah?

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Indian Express

The Karnataka High Court recently upheld the state government’s prohibition on hookahs, deeming hookah bars as an illegal “service” under India’s anti-tobacco law.

- The decision came following challenges by several restaurant owners to the government’s February 7 notification.

Key Highlights

- Constitutional Arguments:

- The government supported its ban citing Article 47 of the Constitution, which mandates the State to elevate public health by prohibiting the consumption of intoxicating drinks and harmful drugs except for medicinal purposes.

- Article 47 is part of Part IV of the Constitution, known as directive principles of state policy.

- Although these principles aren’t enforceable by courts, they’re fundamental in governance, and it’s the State’s duty to apply them in legislation.

- Interpretation of Article 21 and Article 47:

- The High Court highlighted the intrinsic connection between Article 47 and the right to life with dignity enshrined in Article 21.

- It emphasized that it’s the paramount duty of the State to ensure protection to human life and health, constituting a fundamental right under Article 21.

- Restrictions on Fundamental Rights:

- The petitioners contended that the government’s notification infringed upon the fundamental right to engage in any profession, trade, or business as guaranteed by Article 19(1)(g).

- However, the court clarified that this freedom can be subjected to reasonable restrictions, including the prohibition of certain occupations, trades, or businesses, if it serves the general public interest.

- The court asserted that directive principles such as Article 47 can justify limitations on citizens’ rights under Article 19(1)(g).

- It emphasized the importance of balancing individual freedoms with the broader societal interests, particularly in matters concerning public health and well-being.

- OTPA and Rule Framework:

- Under Section 31 of the Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 (COTPA), the Central Government has the authority to establish further Rules to execute the Act.

- Notably, the Prohibition of Smoking in Public Places Rules, enforced in 2008, fall under this jurisdiction.

- Legal Interpretation by Justice Nagaprasanna:

- Justice Nagaprasanna, in his judgment, relied on Rule 4(3) of COTPA, which underwent an amendment in 2017. This rule explicitly states, “No service shall be allowed in any smoking area or space provided for smoking.”

- The court pondered whether hookah smoking should be regarded as simple smoking permitted in designated areas or as a service provided.

- Comparison with Cigarette Smoking:

- To address this query, the court compared hookah smoking with cigarette smoking.

- It noted that smoking zones designated for cigarettes solely provide space without any additional service.

- In contrast, hookah smoking involves the provision of services within the designated area, as it necessitates human intervention to set up the apparatus, akin to serving food or alcohol.

- Based on this analysis, the court concluded that the act of preparing to smoke hookah tobacco inherently constitutes a service.

- Thus, the state’s prohibition is simply enforcing existing restrictions against such services.

- Moreover, the court determined that the notification extends to herbal hookah as well, as it requires specialized instruments, thereby qualifying as a service under the Rules.

- Legal Implications of the Court’s Decision:

- The court’s interpretation elucidates the distinction between simple smoking and the provision of hookah services within designated areas.

- By categorizing hookah preparation as a service, the court reinforces the state’s authority to regulate and restrict such activities in alignment with public health objectives outlined in COTPA and its associated Rules.

About COTPA 2023

- The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 (COTPA) is a significant legislation enacted by the Parliament of India in 2003 to regulate the advertisement, trade, and production of cigarettes and other tobacco products in the country.

- Key provisions of the COTPA Act, 2003 include:

- Smoking Restrictions:

- The Act prohibits smoking of tobacco in public places, except in designated smoking zones in specific establishments like hotels, restaurants, and airports.

- Smoking is restricted in various public places to protect non-smokers from involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke.

- Advertisement Restrictions:

- The Act prohibits the advertisement of tobacco products, including cigarettes.

- It restricts any form of tobacco product advertisement in the media and public spaces. Surrogate advertisement is also prohibited under the Act.

- Sale to Minors:

- Tobacco products cannot be sold to individuals below the age of 18 years.

- Additionally, the sale of tobacco products within a 100-yard radius of educational institutions is prohibited.

- Packaging Regulations:

- The Act mandates that tobacco products must be sold in packages containing appropriate pictorial warnings, information on nicotine and tar contents, and specific health warnings like “Smoking Kills” and “Tobacco Causes Mouth Cancer” in both Hindi and English.

- Enforcement and Penalties:

- The Act empowers police officers and other designated officials to conduct searches and seizures of premises suspected of violating the Act.

- It imposes fines and penalties for various offenses, such as failure to adhere to packaging regulations, smoking in public places, selling tobacco products to minors, and advertising tobacco products.

- Display Requirements:

- Owners or managers of public places where tobacco products are sold must display warning boards indicating “No Smoking Area,” and appropriate messages like “Tobacco Causes Cancer” must be displayed in these establishments.

- The COTPA Act, 2003 repealed The Cigarettes (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 1975, consolidating and strengthening regulations related to tobacco products in India.

- Smoking Restrictions:

Toss out the junk food, bring back the healthy food plate

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

In India, as in many other nations, a significant nutritional transition is underway, characterized by a notable departure from traditional, whole-food-based diets towards more Westernized dietary patterns.

- This shift, coinciding with rapid economic development and urbanization, has led to increased consumption of processed and calorie-dense foods, commonly referred to as “junk foods.”

- These products, lacking in essential nutrients like fiber, vitamins, and minerals, are instead abundant in unhealthy components such as fats, sugars, salt, and various preservatives.

Key Highlights

- Health Implications of Dietary Shift

- The adoption of these Western-style diets, rich in high fats, salts, and sugars (HFSS), has profound health implications for the Indian population.

- Scientific evidence highlights the detrimental effects of junk food consumption, including compromised immune responses, elevated blood pressure, spikes in blood sugar levels, weight gain, and heightened risks of cancer.

- Consequently, India is witnessing a surge in lifestyle diseases, with unhealthy dietary habits emerging as a primary contributing factor.

- Notably, recent studies by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) underscore alarming prevalence rates of metabolic disorders, with significant portions of the population affected by diabetes, hypertension, and abdominal obesity.

- Role of Aggressive Advertising

- A crucial factor shaping evolving dietary behaviors among Indians is the pervasive influence of aggressive advertising campaigns promoting “tasty” and “affordable” comfort foods, particularly targeting younger consumers.

- Research conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reveals that 93% of children ate food that was packaged, 68% drank packaged sweetened beverages more than once a week, and 53% ate these foods at least once a day..

- Moreover, the ultra-processed food industry in India has experienced remarkable growth, fueled by a compound annual growth rate of 13.37% between 2011 and 2021.

- Projections suggest further expansion, with India’s food processing industry poised to reach a substantial $535 billion by 2025-26.

- Legal Framework and Court Ruling

- The Supreme Court of India, in a landmark ruling in 2013, underscored the constitutional significance of protecting public health in the context of food safety.

- The Court’s assertion that hazardous or injurious food articles pose a threat to the fundamental right to life, enshrined in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, laid a solid foundation for regulatory actions aimed at safeguarding consumers from unhealthy foods.

- Government Initiatives for Health Promotion

- The Government of India has demonstrated a commitment to promoting public health and well-being through various initiatives.

- Notable among these are Eat Right India, the Fit India Movement, and the Prime Minister’s Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nutrition (Poshan) 2.0.

- These programs aim to encourage healthier dietary habits and active lifestyles across the population, aligning with the broader goal of improving public health outcomes.

- Regulatory Measures Targeting Children

- Recognizing the vulnerability of children to the influence of unhealthy food advertising, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) introduced regulations in 2020 specifically addressing food safety and balanced diets for children in school environments.

- These regulations impose restrictions on the sale of high fats, salts, and sugars (HFSS) foods in school premises and nearby areas, aiming to create a healthier food environment for children.

- Additionally, recent actions by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights highlight efforts to combat misleading advertisements promoting unhealthy products targeted at children, particularly those disguised as “health drinks” despite their high sugar content.

- Challenges and Strategies for Effective Implementation

- Despite policy intentions to foster a safe food environment, challenges remain in translating these intentions into tangible outcomes.

- Effective implementation of interventions targeting the consumption of junk foods necessitates concerted efforts and strategic approaches.

- Four key strategies emerge as essential for bridging the gap between policy formulation and practical implementation, thereby driving meaningful change on the ground.

- Defining High Fats, Salts, and Sugars (HFSS) Foods

- A crucial aspect of governmental efforts to safeguard children from the adverse effects of junk foods involves defining what constitutes high fats, salts, and sugars (HFSS) foods.

- Despite regulations by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) to restrict the consumption of HFSS foods, the absence of a clear definition poses challenges to effective implementation.

- Therefore, the FSSAI must take the necessary steps to define HFSS foods in the Indian context, facilitating better enforcement of food safety regulations.

- Additionally, institutions like the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights can play a pivotal role in ensuring stricter adherence to regulations governing foods consumed in school environments.

- Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) for Informed Choices

- Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) emerges as a pragmatic approach to empower consumers with information for making informed dietary choices.

- Presently, nutrition information is often relegated to small print on the back of food packages, rendering it inaccessible and incomprehensible to many consumers.

- FOPL, such as a “warning label” indicating high salt content, can significantly enhance consumer awareness, especially among individuals with health conditions like hypertension.

- By drawing attention to key nutritional aspects on the front of packaging, FOPL facilitates informed decision-making regarding food consumption.

- Also, the concept of an Indian Nutrition Rating (INR), wherein packaged food products receive a star rating based on their overall nutritional profile, holds promise in promoting healthier dietary habits.

- However, there are notable concerns regarding its implementation.

- One major issue is the potential for producers to manipulate ratings by adding superficially healthy components while maintaining unhealthy levels of fats, sugars, and salts.

- Moreover, the voluntary nature of regulations surrounding INR poses challenges to its effectiveness, particularly during the initial four-year period following the final notification of regulations.

- Subsidies for Healthy Foods

- One approach to promote healthier dietary habits involves implementing policies that incentivize the consumption of nutritious foods.

- This can be achieved through subsidies aimed at making whole foods, millets, fruits, and vegetables more accessible and affordable, particularly in both rural and urban areas.

- By making nutritious foods more economically viable, subsidies can encourage greater consumption and contribute to improved public health outcomes.

- Behavioral Change Campaigns

- Complementing policy measures, behavioral change campaigns targeting children and young adults can play a pivotal role in fostering healthy dietary habits and promoting mindful eating practices.

- These campaigns may utilize multimedia messaging to educate individuals about the health impacts of junk foods, emphasizing the importance of balanced diets and the consumption of locally sourced, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and traditional foods like millets.

- Urgency of Dietary Shift and People’s Movement

- Recognizing the pressing need to transition towards healthier diets, there is a call for concerted efforts to create public demand for nutritious and diverse food options.

- It is imperative to combine awareness-raising campaigns with genuine policy interventions that empower individuals to exercise their right to choose nutritious foods.

- By fostering a culture of health-consciousness and advocating for policy changes that prioritize public health, India can pave the way for a healthier future.

About the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI)

- The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is a statutory body established under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India.

- It was created in 2008 under the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006, which consolidates various acts and orders related to food safety and standards in India.

- The primary objective of FSSAI is to ensure the availability of safe and wholesome food for human consumption by regulating the manufacture, storage, distribution, sale, and import of food articles.

- FSSAI is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the regulation and supervision of food safety.

- It sets up rules and guidelines for food manufacturing, keeping hygiene and food safety in mind.

- The organization also grants licenses to pursue any food-related business and tests the standard of food.

- Regular inspections and audits are conducted to ensure compliance with food safety regulations.

- The Food Safety Display Board is now required in all food establishments, under FSS Regulations, to display an FSSAI license or registration.

- The FSSAI is also working on Repurpose Spent Cooking Oil (RUCO), a program that enables the collecting and conversion of used cooking oil into biodiesel.

- The administrative structure of the FSSAI includes the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare as the administrative ministry, with a non-executive Chairperson chosen by the Central Government and a CEO appointed by the Government.

- The FSSAI has six regional offices located in Delhi, Guwahati, Mumbai, Kolkata, Cochin, and Chennai.

Towards a less poor and more equal country

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

According to a working paper titled ‘Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj’ by the World Inequality Lab, income inequality in India has reached alarming levels.

- In the fiscal year 2022-23, a staggering 22.6% of the national income was concentrated in the hands of the top 1% of the population, marking the highest level of income concentration in the country in the last century.

- Furthermore, the report highlights that the top 0.1% of the population earned nearly 10% of the national income, indicating an extreme concentration of wealth among a minuscule portion of the population.

- India’s income inequality, as per the report, ranks among the highest globally, surpassing even countries like South Africa, Brazil, and the United States.

Key Highlights

- Wealth Inequality Trends

- The report also sheds light on the concerning trends in wealth inequality within India.

- In 2022-23, the top 1% of the population held a staggering 40.1% share of the national wealth, the highest level since 1961.

- Over the decades, the share of wealth held by the top 10% has steadily increased, rising from 45% in 1961 to 65% in 2022-23.

- Conversely, the share of wealth held by the bottom 50% and middle 40% of the population has witnessed a decline, exacerbating wealth disparities.

- The report highlights a startling statistic, revealing that a mere 10,000 individuals out of 92 million Indian adults own an average wealth equivalent to ₹22.6 billion, underscoring the extreme wealth concentration at the top.

- Comparative Analysis and the ‘Billionaire Raj’

- While India’s wealth inequality is not as extreme as countries like Brazil and South Africa, the concentration of wealth has tripled between 1961 and 2023, posing significant socio-economic challenges.

- The period between 2014-15 and 2022-23 witnessed a notable surge in wealth concentration at the top, earning the moniker ‘Billionaire Raj,’ which the report compares to the colonial-era ‘British Raj.’

- The escalation of inequality undermines both economic growth and poverty reduction efforts.

- Historical Trends and Policy Implications

- Historical analysis reveals a declining trend in inequality between 1960 and 1980, attributed to growth patterns and policy objectives during that period.

- However, inequality began to rise with the onset of liberalization in the 1980s and escalated further following the economic reforms of 1991.

- Interplay of Economic Growth and Inequality

- The relationship between economic growth, income inequality, and human development in India is complex and multifaceted.

- Until 1975, India’s average income, adjusted for inflation and purchasing power differentials, was comparable to that of China and Vietnam.

- However, over the next 25 years, incomes in China and Vietnam surged by 35-50% compared to India’s, setting the stage for divergent growth trajectories.

- Post-2000, China experienced rapid economic expansion, surpassing India’s income by 2.5 times.

- Despite moderate growth rates, India’s economic landscape has been marred by extreme levels of inequality, particularly highlighted by the substantial share of income captured by the top 1%.

- The Case of China and Vietnam

- China’s economic growth has been characterized by broad-based development, contributing to a moderate increase in economic inequality.

- In contrast, India’s growth has been moderate, coupled with a stark rise in economic inequality.

- Consequently, India is labeled as both “poor and very unequal.”

- Achieving high economic growth while simultaneously reducing inequality remains a formidable challenge, echoing the success stories of China and Vietnam, where improvements in human development and poverty reduction preceded economic growth.

- Importance of Human Development

- Human development, encompassing improvements in capability, functioning, and poverty reduction, holds paramount importance in fostering inclusive growth.

- States in India that have sustained high growth rates over three decades typically exhibit advanced levels of human development.

- Conversely, states lagging in human development, such as Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Bihar, have struggled to achieve significant growth post-liberalization.

- India’s Human Development Performance

- India’s performance in human development, as per the Human Development Report (HDR) 2023-2024, ranks lower than countries like Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Bangladesh, despite being the fifth-largest economy globally.

- Economic growth has not translated proportionately into human development gains, underscoring the need for prioritizing inclusive growth strategies.

- Addressing Economic Inequality

- Economic inequality poses a significant challenge to inclusive growth in India, as highlighted by the HDR 2023-2024, which reveals a substantial decrease in India’s human development score when accounting for economic inequality.

- Government initiatives like the Pradhan MantriGaribKalyan Anna Yojana, while beneficial, are insufficient in addressing the magnitude of economic inequality.

- Sustainable and inclusive growth necessitates the creation of meaningful employment opportunities alongside social and political reforms to tackle entrenched inequality effectively.

- Failure to address these disparities may lead to social and political unrest in the long term, underscoring the urgency for comprehensive policy interventions.

An overview of the PMAY-U scheme

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

The Pradhan MantriAwasYojana (PMAY) is a flagship programme of the Union government aimed at achieving “Housing for All” by 2022, encompassing both urban and rural areas.

- Launched in 2015, PMAY is a centrally sponsored scheme requiring financial contributions from both the Union and State governments.

- The scheme aims to address various housing-related challenges, including slum rehabilitation, promoting affordable housing for weaker sections, and providing subsidies for beneficiary-led construction.

Key Highlights

- Execution and Progress of the Scheme

- Despite being a key initiative of the government, the PMAY has faced significant challenges in achieving its objectives.

- As of August 2022, the PMAY-Urban (PMAY-U) has been extended until December 31, 2024, to complete already sanctioned houses.

- However, the scheme’s performance has been underwhelming, with a substantial gap between the intended targets and actual outcomes.

- Government estimates indicate a shortage of approximately 20 million houses in rural areas and three million in urban centers.

- However, these figures may not accurately reflect the ground reality, with the actual shortfall being much higher.

- Data from the PMAY dashboard reveals a shortfall of around 40 lakh houses, highlighting the failure of the scheme to address the pressing need for housing, particularly in urban areas.

- Challenges and Failures

- The PMAY-U has particularly struggled to meet the demand for in-situ slum redevelopment (ISSR), with only a fraction of the targeted houses being sanctioned for eligible beneficiaries.

- Reports suggest that the scheme has only addressed a fraction of the housing shortage, leaving millions of households without adequate housing.

- Despite substantial budgetary allocations, amounting to over $29 billion in the last five years, PMAY has not been able to fulfill its promise of providing “Housing for All.”

- Private Sector Participation

- The Pradhan MantriAwasYojana (PMAY) sought to engage the private sector significantly in addressing the housing deficit, particularly in urban areas where a substantial portion of the population resides in slums.

- The scheme aimed to leverage private investments to complement public efforts in social housing initiatives.

- Challenges in Slum Redevelopment

- Despite the ambitious goals of PMAY, the implementation of slum redevelopment projects faced several challenges.

- In some instances, handing over slum spaces to private developers resulted in vertical growth of settlements, exacerbating problems for residents.

- Multi-storey buildings with recurring utility costs exceeded residents’ financial capacities, while cramped living spaces deterred occupancy.

- Additionally, land ownership issues, particularly with land under airports, railways, and forests, posed significant hurdles for in-situ slum redevelopment (ISSR).

- Discrepancy with City Master Plans

- Another obstacle to the success of PMAY was the discord between city master plans and the scheme’s objectives.

- City plans, influenced by consultants favoring capital-intensive solutions like transit-oriented development, often neglected social housing components, leaving PMAY initiatives unsupported and ineffective.

- Financial Architecture of PMAY

- The financial structure of PMAY raised concerns about its effectiveness in addressing the needs of the landless and poor.

- While the Centre’s contribution amounted to only 25% of the total investment expenditure, beneficiary households bore the bulk of the financial burden, contributing 60% of the total expenditure.

- State governments also made substantial investments, but the architecture of PMAY favored certain segments over others.

- The BLC vertical, for example, received significant attention, with the government’s role limited to cost-sharing, leaving issues like land ownership largely unaddressed.

- Similarly, the limited involvement of the government in providing interest subsidies for CLSS beneficiaries and the small proportion of slum-dwelling families benefiting from ISSR underscored the scheme’s inadequacies in catering to the most vulnerable populations.

About the Pradhan MantriAwasYojana (PMAY)

- The Pradhan MantriAwasYojana (PMAY) is a credit-linked subsidy scheme initiated by the Government of India to facilitate access to affordable housing for low and middle-income groups.

- Launched in June 2015, PMAY aims to construct 2 crore affordable houses by March 2022, with two components:

- Pradhan MantriAwasYojana (Urban) for urban poor and Pradhan MantriAwaasYojana (Gramin) for rural areas.

- The scheme integrates with other initiatives to ensure houses have basic amenities like toilets, electricity, and water supply.

- PMAY-Urban, a major flagship program under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, covers all urban areas in India.

- It operates through four verticals: Beneficiary Led Construction/Enhancement, Affordable Housing in Partnership, In-situ Slum Redevelopment, and Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme.

- The scheme ensures that all houses have essential amenities and promotes women empowerment by providing house ownership to female members.

- It also prioritizes vulnerable sections of society like differently-abled persons, senior citizens, and minorities.

- The implementation of PMAY-G is carried out by the Ministry of Rural Development.

- The scheme aims to provide a pucca house with basic amenities to all homeless people and those living in kutcha houses or severely damaged houses by 2024.

How is India planning to boost EV production?

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : The Hindu

On March 15, the Union government approved a policy aimed at promoting India as a manufacturing hub for electric vehicles (EVs).

- The policy seeks to attract global EV manufacturers to invest in India and establish local manufacturing operations.

- The government highlights that this initiative will not only provide Indian consumers access to the latest EV technology but also contribute to the Make in India initiative, fostering competition among EV players and ultimately leading to higher production, economies of scale, and reduced air pollution.

Key Highlights

- Key Provisions of the Policy

- The policy sets a minimum investment requirement of ₹4,150 crores and aims to achieve two primary objectives:

- localizing production and achieving an annual EV car sale of 30% by 2030.

- It provides a framework for global EV manufacturers, such as Tesla and BYD, to enter the Indian market and establish local manufacturing facilities.

- The central goal is to facilitate the transition to localized production in a commercially viable manner, tailored to local market conditions and demand.

- Reduction of Import Duty on EVs

- A significant provision of the policy is the reduction of import duty on electric vehicles imported as completely built units (CBUs) with a minimum cost, insurance, and freight (CIF) value of $35,000.

- The import duty is lowered from the current 70%-100% to 15%.

- This move aims to incentivize the import of EVs and facilitate their entry into the Indian market.

- Extension and Conditions

- Under the policy, the current provision will be extended for five years, contingent upon manufacturers establishing their facilities in India within three years.

- This incentivizes timely investment in local manufacturing infrastructure while ensuring the continuity of import subsidies for a defined period.

- Waiver of Import Duty

- The policy stipulates a total duty waiver of ₹6,484 crore or a proportional amount based on the investment made by manufacturers, whichever is lower, on the total number of EVs imported.

- This provision encourages the import of EVs while linking duty waivers to investment commitments, thereby aligning incentives with investment objectives.

- Import Limits and Investment Criteria

- Import under the scheme is capped at 40,000 EVs, not exceeding 8,000 units annually, provided a minimum investment of $800 million is made.

- Unused annual import limits can be carried over.

- The minimum investment threshold for eligibility is set at $500 million (approximately ₹4,150 crore), ensuring substantial commitments from manufacturers.

- Localization Targets

- Manufacturers are required to establish their manufacturing facilities in India within three years and achieve 25% localization by the third year and 50% by the fifth year of incentivized operation.

- Localization targets focus on domestic value addition within the manufacturing process.

- Failure to meet localization targets or minimum investment criteria may result in the invocation of manufacturers’ bank guarantees.

- Impact on Domestic Players

- Industry experts suggest that the policy primarily benefits Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) catering to the higher end of the market, as most Indian players currently lead in segments below ₹29 lakhs.

- It is believed the policy incentivizes global EV players and Indian joint ventures with such players to expand sales and manufacturing in India.

- This expansion would facilitate technology transfer and upgrades in the local supplier ecosystem, benefiting both global and local manufacturers.

- However, some global OEMs in the luxury segment, already planning to localize their EVs in India, may face a disadvantage.

- Challenges in EV Adoption

- EV penetration has been significant in the two and three-wheeler segments, passenger vehicles have only contributed 2.2% so far.

- This is attributed to factors such as inadequate charging infrastructure, range anxiety, and a limited number of affordable products due to insufficient localization.

- Importance of Charging Infrastructure

- Scaling up charging infrastructure is crucial for increasing EV adoption.

- The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) estimates that India may need at least 13 lakh charging stations by 2030 to support aggressive EV uptake.

- Challenges for Global Players

- Global players entering the Indian market must ensure the availability of quality products at affordable prices, supported by reliable charging infrastructure and driving range.

- These players face the task of adapting to a market that has relied heavily on government incentives.

- The policy sets a minimum investment requirement of ₹4,150 crores and aims to achieve two primary objectives:

NABARD unveils strategy to mobilise green financing

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : The Hindu

NABARD, in commemoration of Earth Day, revealed its Climate Strategy 2030 document, aimed at addressing India’s urgent need for green financing.

- The strategy highlights the inadequacy of current green finance inflows, citing that India requires approximately $170 billion annually to achieve a cumulative total of over $2.5 trillion by 2030.

- Despite garnering about $49 billion in green financing as of 2019-20, a mere fraction of the required amount, the majority of funds were allocated for mitigation purposes.

- Adaptation and resilience efforts received only $5 billion, indicating limited private sector engagement due to challenges in bankability and commercial viability.

Key Highlights

- The Climate Strategy 2030 is structured around four key pillars:

- Accelerating Green Lending: NABARD aims to boost green lending across sectors to meet the growing demand for sustainable financing.

- Market-Making Role: The strategy involves playing a broader role in shaping the market to encourage more sustainable investment practices.

- Internal Green Transformation: NABARD commits to its internal green transformation to align with sustainability goals.

- Strategic Resource Mobilisation: The strategy focuses on mobilising resources strategically to support green initiatives effectively.

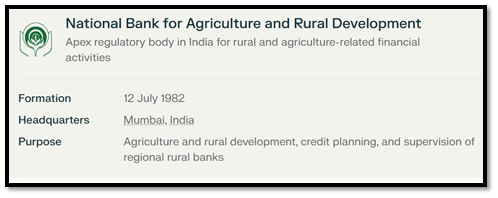

About NABARD

- National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) is a development bank established in India on July 12, 1982, under the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development Act.

- NABARD is fully owned by the Government of India and is headquartered in Mumbai, India.

- It has a mandate to promote sustainable and equitable agriculture and rural development in India.

- NABARD is responsible for providing and regulating credit and other facilities for the promotion and development of agriculture, small-scale industries, cottage and village industries, handicrafts, and other rural crafts and allied economic activities in rural areas with a view to promoting integrated rural development and securing prosperity of rural areas.

- NABARD provides financial assistance to the State Governments for projects covering 39 activities broadly classified under Agriculture & Related Sector, Social Sector, and Rural Connectivity.

- It also provides refinancing facilities to rural financial institutions, including cooperative banks and regional rural banks, to enable them to meet the credit needs of the rural population.

- NABARD is also responsible for implementing the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF), which provides long-term finance to State Governments for rural infrastructure projects.

- NABARD also implements the Micro Irrigation Fund (MIF) to expand micro-irrigation coverage in the country.

- NABARD is also responsible for promoting and developing rural financial institutions, including cooperative banks and regional rural banks, and for providing them with refinancing facilities to enable them to meet the credit needs of the rural population.