CURRENT AFFAIRS – 18/12/2023

- CURRENT AFFAIRS – 18/12/2023

- LEADS (Logistics Ease Across Different States) 2023 report

- International School of Peace and Happiness to Open in Assam’s Bodoland Territorial Region

- Global coal demand expected to decline by 2026: IEA report

- An uphill struggle to grow the Forest Rights Act

- On selecting Election Commissioners

- An overview of the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act

- Bhutan to have 1,000-sq. km. green city along Assam border

- Kakrapar-4 nuclear reactor attains criticality

CURRENT AFFAIRS – 18/12/2023

LEADS (Logistics Ease Across Different States) 2023 report

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : The Indian Express

The Commerce and Industry Ministry released the Logistics Index Chart 2023, categorizing Indian states and Union Territories based on their logistics efficiency, crucial for export promotion and economic growth.

- The report emphasizes key challenges faced by stakeholders and includes recommendations to enhance logistics performance.

Key Highlights

- Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Chandigarh, and Gujarat retained their “achievers” status in the Logistics Index Chart 2023, as per the report from the Commerce and Industry Ministry.

- The total number of achievers decreased from 15 to 13 this year, with Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand moving into the “aspirers” and “fast movers” categories, respectively.

- Sikkim and Tripura advanced from the “fast movers” category in 2022 to join the ranks of “achievers” in the latest assessment.

- Besides the aforementioned states, Delhi, Assam, Haryana, Punjab, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh were recognized as “achievers” in the logistics domain.

- Fast Movers and Aspirers:

- Kerala, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Andaman and Nicobar, Lakshadweep, and Puducherry were classified as “fast movers.”

- “Aspirers” include Goa, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

Note: The is the fifth LEADS (Logistics Ease Across Different States) 2023 report that ranks states based on their logistics ecosystem. The first logistics report was released in 2018.

International School of Peace and Happiness to Open in Assam’s Bodoland Territorial Region

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : TH

In a pioneering move, the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) in Assam is set to establish the International School of Peace and Happiness in Bijni, Chirang district, as part of the Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR).

- The school aims to impart lessons on humanity and societal happiness, marking a significant step towards fostering peace in a region historically plagued by conflicts.

Key Highlights

- The foundation of the International School of Peace and Happiness is slated to be laid in the first week of January 2024.

- Located in Bijni, western Assam’s Chirang district, the initiative follows a year of planning by the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC).

- Vision Behind the School:

- The concept of the school specializing in peace-building and happiness promotion emerged from the BTC government’s collaboration with the United People’s Party Liberal, BJP, and the Gana Suraksha Party over the past three years.

- Educational Objectives:

- The school aims to provide formal education focusing on human values, cultivating a generation of peace ambassadors capable of addressing conflicts at both micro and macro levels.

- Emphasis on youth and community leaders as recipients of this unique educational approach to contribute to conflict resolution.

- The initiative signifies a long-term commitment to building a foundation for peace and happiness within the BTR, potentially serving as a model for conflict-prone regions globally.

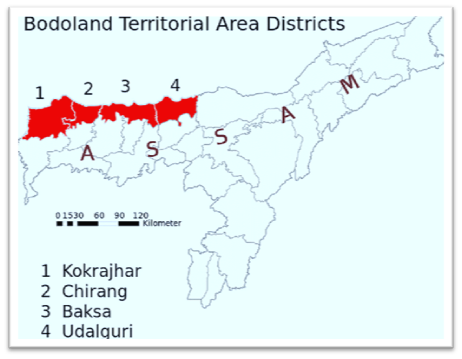

About Bodoland Territorial Region

- The Bodoland Territorial Region, commonly known as Bodoland, is an autonomous region situated in Assam, Northeast India.

- Comprising four districts on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river, below the foothills of Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh, the region covers over nine thousand square kilometers.

- Administrative Structure:

- Bodoland is administered by the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC), an elected body established under a peace agreement signed in February 2003.

- The autonomy of Bodoland was further extended through an agreement signed in January 2020.

- Official Languages: Bodo, English, Assamese.

- Geographical and Demographic Characteristics:

- Geographically, Bodoland is located in the northeastern part of Assam, characterized by its proximity to the Brahmaputra river and the bordering foothills.

- The region is predominantly inhabited by the Bodo people and other indigenous communities of Assam.

- Origins of Bodoland:

- The demand for a separate union territory for the Boro and other plain tribes, initially named Udayachal, was voiced by the Plains Tribes Council of Assam in 1967.

- In 1987, the All Bodo Students’ Union initiated the Bodo Movement, seeking a separate state known as Bodoland.

- The movement concluded with the Bodo Accord of 1993, leading to the formation of the Bodoland Autonomous Council.

- The name “Bodoland” is derived from “Bodo,” an alternate spelling referring to the Boro people, primarily residing in the Dooars regions of Goalpara and Kamrup districts.

- The establishment of Bodoland and the subsequent autonomy agreements are rooted in historical movements and accords, addressing the aspirations of the Bodo community and other plain tribes in the region.

Note: Bodos are the single largest community among the notified Scheduled Tribes in Assam. They constitute about 5-6% of Assam’s population.

About Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC)

- The Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) is an autonomous council established for the Bodoland Territorial Region under the 6th Schedule of the Constitution of India.

- Its formation is outlined in the Memorandum of Settlement between the Bodoland Liberation Tiger Force (BLTF) and the Governments of India and the Government of Assam.

- Composition and Jurisdiction:

- The BTC consists of 40 elected members, and an additional six members are appointed by the Governor of Assam.

- The designated area under the BTC’s authority is officially termed the Bodoland Territorial Area District (BTAD).

- The Bodoland Territorial Council is led by a Speaker, overseeing its legislative functions.

- The executive committee is chaired by a Chief Executive Member, with PramodBoro currently occupying this role.

The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution of India

- The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution of India provides special provisions for the administration of tribal areas in the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

- The provisions of the sixth schedule are provided under Articles 244(2) and 275(1) of the Indian Constitution.

- They were formulated based on the recommendations of the Bardoloi Committee.

- It grants autonomy to the tribal communities in these regions, allowing them to have a certain degree of self-governance.

- The areas under the Sixth Schedule are divided into autonomous districts, and each autonomous district is further subdivided into autonomous regions.

- The administration of these areas is carried out by the District Councils and Regional Councils, which have legislative, executive, and financial powers.

- The District Councils have the authority to make laws on various subjects, including land, forests, management of markets, money lending and agricultural practices, education, and health.

- Governor’s Empowerment:

- The Governor of the State holds the power to determine administrative units within Autonomous Districts and Regions.

- Authority is granted to create new Autonomous Districts/Regions and modify their territorial jurisdiction or names.

- In cases of diverse tribal populations within an autonomous district, the Governor has the authority to divide it into multiple autonomous regions.

Global coal demand expected to decline by 2026: IEA report

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : TH

A recent report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts a decline in global coal demand by 2026, despite reaching an all-time production high in 2023.

- The shift is attributed to increasing reliance on renewables, plateauing demand from China, and evolving climate conditions.

Key Highlights

- The report forecasts a 1.4% increase in global coal demand in 2023, surpassing 8.5 billion tonnes for the first time.

- Regional Disparities:

- The demand for coal is expected to drop by 20% in the European Union and the United States.

- Conversely, demand is projected to increase by 8% in India and 5% in China, primarily driven by electricity demand and reduced hydropower generation.

- Factors Influencing Decline:

- The anticipated decline in coal demand is attributed to the rise in renewable energy capacity globally.

- The report notes that changing climate conditions, from El Nino to La Nina, could lead to improved rainfall during 2024-2026, enhancing hydropower output.

- The upward trend in low-cost solar photovoltaic deployment is expected to contribute significantly to renewable power generation.

- Moderate increases in nuclear power generation, particularly in China, India, and the European Union, are expected to further diminish coal-fired generation.

- With China’s ambitious plans for renewable energy expansion, coal demand in the country is expected to fall in 2024 and plateau by 2026.

- Overall, this will result in a 2.3% fall in global call demand by 2026.

- Global Coal Consumption Challenges

- Coal, a crucial energy source for electricity, steel, and cement industries, also stands as the primary contributor to human-induced carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

- Despite projections of a decline, a market report indicates that global coal consumption is expected to surpass 8 billion tonnes until 2026.

- As the largest source of CO2 emissions from human activities, coal’s environmental impact is significant.

- International Climate Targets and Coal Reduction:

- Reduction in unabated coal use, burning without carbon capture technologies, is a key agreement among countries under the UNFCCC, a major influencer of global climate policy.

- To limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C by the end of the century, coal emissions must decrease by nearly 95% between 2020 and 2050.

- China, India, and Indonesia, the three largest global coal producers, are expected to achieve record production levels in 2023.

- These three nations collectively contribute to over 70% of the world’s coal production.

About the International Energy Agency (IEA)

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is an autonomous intergovernmental organization established in 1974 within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- The IEA was created in response to the oil crisis of 1973-1974, with the primary objective of promoting energy security among its member countries and coordinating responses to disruptions in the supply of oil.

- Formation and Mandate:

- The IEA was established on November 18, 1974, in response to the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC).

- Its mandate is to promote energy security, economic growth, and environmental sustainability among its member countries.

- Membership:

- The IEA started with an initial membership of 18 countries and has since expanded. As of my last knowledge update in January 2022, the IEA has 31 member countries.

- Headquarters:

- The agency is headquartered in Paris, France.

- Energy Security:

- One of the core missions of the IEA is to enhance the collective energy security of its member countries.

- This involves developing policies to respond to energy supply disruptions and maintaining emergency oil stocks.

- The World Energy Outlook is one of the flagship publications of the IEA, providing comprehensive insights into the future of the global energy landscape.

An uphill struggle to grow the Forest Rights Act

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : TH

The Forest Rights Act (FRA), also known as the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, was endorsed by the Rajya Sabha on December 18, 2006.

- This legislation aimed to resolve conflicts over alleged ‘forest encroachments’ and establish a more democratic, bottom-up approach to forest governance. However, challenges in implementation have hindered the realization of its objectives.

Key Highlights

- Pre-Colonial Forest Rights:

- Local communities traditionally held customary rights over forests before colonial rule.

- Kings or chieftains might claim specific rights, but communities retained other forest benefits.

- Colonial Disruption:

- The colonial takeover, guided by the 1878 Indian Forest Act, disrupted these traditions.

- The Imperial Forest Department prioritized timber and revenue, treating local communities as trespassers.

- Shifting cultivation was banned as forests were perceived primarily as timber resources.

- Survey and settlement of agricultural lands favored the state, contributing to injustices.

- ‘Forest villages’ were established, leasing forest land to households (mainly Adivasi) for compulsory labor.

- Access to forest produce became limited, temporary, and chargeable, subject to forest bureaucracy control.

- Local communities had no right to manage the forest as state control prevailed, logging valuable forests.

- Forest Rights Act (FRA) as a Response:

- Enacted in 2006, the FRA aimed to rectify historical injustices, recognize forest-dwellers’ rights, and democratize forest governance.

- Challenges in FRA Implementation:

- Implementation hindered by political opportunism, exploiting the Act for vested interests.

- Resistance from foresters resisting changes to established power dynamics.

- Bureaucratic apathy and reluctance to embrace the Act’s transformative goals.

- Discourse marred by deliberate misconceptions, impeding understanding and support for the FRA.

- Post-Independence Challenges:

- Forest areas in princely states and zamindari estates were hastily declared state property during post-Independence assimilation, leading to the labeling of legitimate residents as ‘encroachers.’

- Forest lands were leased for initiatives like the ‘Grow More Food’ campaign without subsequent regularization.

- Communities displaced by dams had no alternative lands and ended up ‘encroaching’ on forest land.

- Forest exploitation continued under the guise of national interest.

- Wildlife Protection Act and Forest Conservation Act:

- The Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972 and the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980, framed within the eminent domain concept, caused further injustices.

- Forced resettlement occurred during the creation of sanctuaries and national parks.

- Development projects ‘diverted’ forests without considering local views or obtaining consent, and compensation for affected communities was lacking.

- Forest Rights Act (FRA) as a Redress:

- The FRA acknowledges historical injustices, both colonial and post-Independence, in the treatment of forest-dwelling communities.

- Recognizes Individual Forest Rights (IFRs) to allow habitation and cultivation existing before December 2005.

- Forest villages to be converted into revenue villages after full rights recognition.

- Recognizes village communities’ rights to access and use forests, own and sell minor forest produce, and importantly, manage forests within customary boundaries.

- Ensures decentralized forest governance, linking authority and responsibility to community rights.

- Lays down a democratic process for identifying the need to curtail or extinguish community rights for wildlife conservation.

- Community rights over a forest provide a say, if not a veto, in any diversion of that forest, with a right to compensation if diverted.

- Supreme Court Affirmation and Challenges:

- The Supreme Court, in the Niyamgiri case, reaffirms the right of communities to have a say in forest diversion and a right to compensation.

- Challenges arise with the Forest Conservation Rules 2022 and FCA Amendment 2023 attempting to bypass these rights.

- Distortions in Implementation:

- Many states focused on individual rights, portraying the Forest Rights Act (FRA) as an ‘encroachment regularization’ scheme.

- Some politicians encouraged illegal new cultivation in certain areas.

- Recognition of IFRs was compromised by resistance from the Forest Department, apathy from other departments, and technology misuse.

- Claimants faced hardships during filing, encountering faulty rejections and arbitrary partial recognitions.

- Imposing digital processes, like the VanMitra software in Madhya Pradesh, in areas with poor connectivity and literacy added to the injustice.

- The issue of ‘forest villages’ has not been adequately addressed in most states.

- Incomplete Recognition of Community Rights:

- Recognition of Community Forest Rights (CFRs) has been extremely slow and incomplete.

- The forest bureaucracy, still structured in a colonial manner, strongly opposes these rights, fearing a loss of control.

- Forest bureaucracy resistance hampers CFR recognition, with estimates suggesting that 70%-90% of central Indian forests should be under CFRs.

- Limited Recognition States:

- Maharashtra, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh are among the few states recognizing CFRs, but only Maharashtra enables their activation by de-nationalizing minor forest produce.

- Even in states recognizing community rights, densely forested potential mining areas may face illegal non-recognition, leading to protests.

- Non-recognition of community rights serves the interests of hardline conservationists and the development lobby.

- Communities in Protected Areas become vulnerable targets for ‘voluntary rehabilitation,’ and forests can be handed over for mining or dams without community consent.

- Understanding the Intent of the Forest Rights Act (FRA)

- Calls to shut down the implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) have emerged as political regimes change, and the memory of the struggles that led to its passage fades.

- Some states talk of ‘saturating’ rights recognition in a mission mode, aiming for widespread implementation.

- Examples from Chhattisgarh indicate that mission mode implementation can inadvertently play into the hands of the Forest Department.

- This leads to distorted rights recognition and the reinstatement of technocratic control.

- It is crucial for political leaders, bureaucrats, and environmentalists to appreciate the spirit and intent of the FRA.

- Without such understanding, historical injustices will persist, forest governance will remain undemocratic, and the potential for community-led forest conservation and sustainable livelihoods will go unrealized.

About the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006

- The Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006, is officially known as the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act.

- The primary aim of the FRA is to recognize and vest forest rights and occupation in forest land to forest-dwelling communities, including Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers, who have been residing in and depending on the forests for generations.

- The Forest Rights Act was enacted on December 18, 2006, and came into force on December 31, 2007.

- The act applies to Forest Dwelling Scheduled Tribes (FDST) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFD) with longstanding residence in these forests.

- The FRA aims to balance forest conservation with the livelihood and food security of FDST and OTFD.

- Key Features:

- Title Rights:

- FDST and OTFD are granted ownership rights to the land they cultivate, with a maximum limit of 4 hectares.

- Ownership is confined to the land currently under cultivation, and no new lands are allocated.

- Use Rights:

- Forest dwellers have rights to extract Minor Forest Produce and utilize grazing areas, among other use rights.

- Relief and Development Rights:

- Provision for rehabilitation in cases of illegal eviction or forced displacement.

- Entitlement to basic amenities, with certain restrictions in place for the sake of forest protection.

- Forest Management Rights:

- Communities have the right to protect, regenerate, conserve, and manage any community forest resource that they have traditionally safeguarded for sustainable use.

- The Gram Sabha holds the authority to initiate the process of determining the nature and extent of Individual Forest Rights (IFR) or Community Forest Rights (CFR) for FDST and OTFD.

- Title Rights:

On selecting Election Commissioners

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : TH

The Rajya Sabha recently passed The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners Bill, 2023, addressing the appointment procedures for the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and Election Commissioners (ECs) in India.

- This legislative move comes in response to a Supreme Court ruling highlighting the absence of a parliamentary law for appointments, emphasizing the need for an independent and transparent mechanism.

Key Highlights

- Constitutional Provision:

- Article 324 of the Indian Constitution outlines the composition of the Election Commission of India (ECI), comprising the CEC and two ECs.

- While the Constitution mandates the President’s appointment authority, it lacks specific provisions for ensuring independence during the appointment process.

- Supreme Court’s Intervention:

- A Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in 2015 urged the Supreme Court to establish an independent, collegium-like system for appointing the CEC and ECs.

- In March 2023, the Supreme Court acknowledged a legislative void over 73 years and stressed the importance of an independent appointment process for upholding the ECI’s integrity.

- It cited the precedents of other democratic institutions with independent appointment mechanisms.

- Committee-Based Appointment Mechanism:

- Building on recommendations from the Dinesh Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms (1990) and the Law Commission’s 255th report (2015), the Supreme Court mandated a committee for CEC and EC appointments.

- The committee comprises the Prime Minister, Chief Justice of India (CJI), and the Leader of the Opposition or the largest Opposition party in the Lok Sabha.

- This mechanism is to remain in effect until Parliament enacts a dedicated law on the matter.

- Legislative Response:

- In response to the Supreme Court’s directive, the Rajya Sabha passed The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners Bill, 2023.

- The proposed legislation aims to establish a comprehensive framework for the appointment, conditions of office, and terms of office for the CEC and ECs.

- Upon passage in the Lok Sabha during the current winter session, it is expected to become law, formalizing the committee-based appointment process and addressing the longstanding legislative vacuum.

- The Proposed Law

- The proposed law, “The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners Bill, 2023,” outlines a structured mechanism for the appointment of the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and Election Commissioners (ECs) in India.

- While it introduces a committee-based selection process, it deviates from the Supreme Court’s recommendations in the AnoopBaranwal case, raising considerations about the level of independence in the appointment process.

- Key Provisions of the Proposed Law:

- Eligibility Criteria:

- The CEC and ECs must be individuals who currently hold or have held a position equivalent to the rank of Secretary to the Government of India.

- Search Committee:

- A search committee, led by the Minister of Law and Justice, is tasked with preparing a panel of five individuals for consideration by the selection committee.

- Selection Committee:

- The President, upon the recommendation of the selection committee, consisting of the Prime Minister, the Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha, and a Union Cabinet Minister nominated by the Prime Minister, appoints the CEC and ECs.

- Exclusion of Chief Justice of India (CJI):

- Notably, the proposed law excludes the CJI from the selection process, departing from the Supreme Court’s earlier directive in the AnoopBaranwal case.

- Global Best Practices:

- The international practices for the selection and appointment of members to electoral bodies vary.

- For instance, in South Africa, it involves the President of the Constitutional Court and representatives of human rights and gender equality.

- The U.K. requires approval from the House of Commons, while in the U.S., the President makes appointments subject to Senate confirmation.

- Critique and Considerations:

- While the proposed Bill introduces a committee-based approach, it is perceived as leaning towards the incumbent government, raising concerns about independence.

- The exclusion of the CJI from the selection committee deviates from the Supreme Court’s recommendations, prompting considerations about the level of independence in the appointment process.

- The proposed law’s enactment could instill public confidence if selections under the new mechanism are made by unanimous decisions by the selection committee.

- Eligibility Criteria:

An overview of the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : TH

The European Union’s (EU) Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act is a comprehensive legislative initiative designed to regulate AI technologies within the EU.

- The legislation aims to address the growing influence of AI across sectors while promoting responsible and ethical development.

Key Highlights

- Objectives of the EU AI Act:

- Create a regulatory framework for AI technologies within the EU.

- Mitigate risks associated with AI systems by categorizing applications into different risk levels.

- Establish clear guidelines for developers, users, and regulators regarding the responsible use of AI.

- Strengths of the EU AI Act:

- Risk-Based Approach:

- The legislation adopts a risk-based approach, categorizing AI applications into different risk levels.

- This flexibility allows tailored regulations, with higher-risk applications subject to more stringent requirements.

- Prohibition of Unacceptable Practices:

- Explicitly prohibits certain AI practices considered unacceptable, such as social credit scoring systems for government purposes, predictive policing applications, and AI systems manipulating individuals.

- Emphasis on Transparency and Accountability:

- Requires developers to provide clear information about AI system capabilities and limitations, ensuring users can make informed decisions.

- Mandates developers to maintain comprehensive documentation to facilitate regulatory oversight.

- Introduces the concept of independent conformity assessment for higher-risk AI applications, enhancing objectivity and reducing the risk of conflicts of interest.

- Risk-Based Approach:

- Limitations of the EU AI Act:

- Definitional Challenges:

- Critics highlight the difficulty in accurately defining and categorizing AI applications.

- The evolving nature of AI technologies may lead to uncertainties in establishing clear boundaries between different risk levels, posing challenges in regulatory implementation.

- Impact on Global Competitiveness:

- Stringent regulations in the EU are criticized for potentially hindering the competitiveness of European businesses in the global AI market.

- Concerns exist that overly restrictive measures might stifle innovation and drive AI development outside the EU.

- Compliance with the EU AI Act may impose a significant burden on smaller businesses and start-ups.

- The resources required for conformity assessments and documentation may disproportionately affect smaller players in the AI industry, limiting their ability to compete with larger counterparts.

- Critics argue that the EU AI Act may lean too heavily towards stringent controls, and striking the right balance between regulation and fostering innovation is crucial.

- Definitional Challenges:

- Potential Implications of the EU AI Act:

- The EU AI Act is expected to have a global impact, influencing the development and deployment of AI technologies beyond the EU.

- As a major economic bloc, the EU’s regulatory framework may set a precedent for other regions, shaping global AI development.

- Prioritizing ethical considerations and fundamental rights, the EU AI Act contributes to the establishment of global norms for AI development.

- The impact on innovation and competitiveness will depend on the balance struck by the EU between regulation and fostering a conducive environment for AI development.

- The Act encourages collaboration and cooperation between regulatory authorities, fostering a unified approach to AI regulation.

- International collaboration is deemed essential to address global challenges and ensure consistent standards across borders.

- Administrative Side of the EU AI Act:

- Individuals have the right to report instances of non-compliance with the EU AI Act.

- Market surveillance authorities of EU member states will enforce the AI Act.

- Specific limits on fines applicable to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups.

- Establishment of a centralised ‘AI office’ and ‘AI Board’ for oversight and governance.

- Fines for businesses not adhering to the EU AI Act range from $8 million to almost $38 million, based on the violation’s nature and the company’s size.

- Fines may be up to 1.5% of the global annual turnover or €7.5 million for providing incorrect information, up to 3% of the global annual turnover or €15 million for general violations, and up to 7% of the global annual turnover or €35 million for prohibited AI violations.

- The EU AI Act is expected to have a global impact, influencing the development and deployment of AI technologies beyond the EU.

Bhutan to have 1,000-sq. km. green city along Assam border

(General Studies- Paper II and III)

Source : TH

Bhutan’s King Jigme KhesarNamgyelWangchuck announces the ambitious “GelephuSmartcity Project” during an address at Changlimathang stadium in Thimpu.

- The project is being described as an “economic corridor connecting South Asia with Southeast Asia via India’s northeastern States.”

Key Highlights

- Scope of the Project:

- The international city will cover an area of over 1,000 sq. km. on the Bhutan-Assam border.

- Pitched as an “economic corridor connecting South Asia with Southeast Asia via India’s northeastern States.”

- Aims to attract quality investment from specially screened international companies.

- Connectivity and Railway Line:

- Acknowledges India’s support in building the first India-Bhutan railway line to Gelephu.

- The railway line will connect with roadways and border trading points into Assam and West Bengal, providing access to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Singapore over time.

- Gelephu Smartcity Features:

- Expected environmental standards and sustainability as a goal.

- Inclusion of an international airport (Bhutan’s second) capable of landing larger planes.

- Focus on “zero emission” industries, a “mindfulness city” catering to tourism and wellness, and infrastructure development.

- Gelephu to be designated as a “Special Administrative Region” governed by different laws to facilitate international investment.

- Strategic Significance:

- Positioned as a transformative period for South Asia with immense growth opportunities.

- Bhutan’s aim is to tap into markets, capital, ideas, and technology for economic transformation.

- Acknowledges India’s role as a key partner in the project.

- Bhutan’s King Jigme KhesarNamgyelWangchuck emphasizes the historical importance of the GelephuSmartcity Project, terming it an “inflection point” for the country.

- The project signifies a crucial moment in history for Bhutan’s economic transformation.

- International Collaboration:

- King Jigme Wangchuck acknowledges the support and commitment of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Government of India for infrastructure development, railway connectivity, and road improvements.

- The King engaged with prominent Indian industrialists, including MukeshAmbani, Gautam Adani, Tata, Birla, and Mahindra group representatives during visits to India.

- Economic Challenges and UN Status:

- The announcement follows the United Nations’ decision to declare Bhutan no longer a Least Developed Country (LDC).

- Despite the achievement, economic challenges persist, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, hydropower project indebtedness, tourism revenue cuts, leading to a downturn with GDP at about 4.3% and unemployment at 20%.

- Migration of Bhutanese youth and professionals to other countries in search of opportunities.

Bhutan Overview

- Geography:

- Bhutan, a landlocked country in South Asia, is located in the eastern Himalayas.

- Bordered by China to the north and India to the south, east, and west, it enjoys a strategic location between the two Asian giants.

- The country’s diverse topography includes mountains, valleys, and rivers, contributing to its unique and picturesque landscapes.

- Culture:

- Bhutan has a rich cultural heritage deeply rooted in Mahayana Buddhism.

- The architecture reflects traditional Bhutanese styles, with distinctive dzongs (fortresses), monasteries, and prayer flags dotting the landscape.

- The Bhutanese people celebrate traditional festivals (tsechus) with colorful masked dances, showcasing their cultural identity.

- Economy:

- Bhutan’s economy is predominantly agrarian, with agriculture employing a significant portion of the population.

- The hydropower sector is a key contributor to the economy, as Bhutan harnesses its abundant water resources for energy production.

- Tourism is another important sector, with Bhutan’s policy of “High-Value, Low-Impact” tourism ensuring sustainable and culturally enriching experiences for visitors.

- Relations with India:

- Bhutan and India share strong historical, cultural, and economic ties.

- The Treaty of Friendship between Bhutan and India, first signed in 1949, establishes close diplomatic and economic cooperation.

- India has played a crucial role in Bhutan’s development, supporting infrastructure projects, education, and healthcare.

Kakrapar-4 nuclear reactor attains criticality

(General Studies- Paper III)

Source : TH

The fourth unit of the Kakrapar Atomic Power Project (KAPP-4) in Gujarat, boasting a 700 MWe capacity, successfully achieved controlled fission chain reaction, marking its criticality at 1.17 am on December 17.

- Situated approximately 80 km from Surat, KAPP-4 stands as a significant milestone for the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL), representing the largest indigenous nuclear power reactors constructed by the public sector NPCIL.

Key Highlights

- 700 MWe Units – Indigenous and Remarkable:

- The 700 MWe units at KAPP are noteworthy as the largest indigenous nuclear power reactors developed by NPCIL, a vital arm of the Department of Atomic Energy.

- These pressurized heavy water reactors (PHWRs) utilize natural uranium as fuel and heavy water as a coolant and moderator.

- KAPP-4’s achievement follows the successful commercial electricity generation by the 700-MWe unit-3 of KAPP, which commenced on August 30.

- The reactors’ operational significance lies in their design, construction, commissioning, and operational capabilities, showcasing NPCIL’s comprehensive expertise in nuclear power generation.

- Safety Features and Industry Collaboration:

- The indigenously built 700 MWe reactors are lauded for advanced safety features, including a steel lining and a passive decay heat removal system.

- Indian industries played a crucial role, supplying equipment and executing contracts for the reactors.

- NPCIL’s Nuclear Power Portfolio:

- NPCIL presently operates 23 nuclear electricity reactors with a total capacity of 7,480 MWe.

- With nine units, including KAPP-4, under construction, and 10 more reactors in the pre-project phase, NPCIL continues to bolster India’s nuclear power capabilities.

About Pressurized Heavy Water Reactors (PHWRs)

- PHWRs are a type of nuclear reactor commonly used for generating electricity.

- They belong to the category of thermal-neutron-spectrum reactors.

- Moderator and Coolant:

- Heavy water (deuterium oxide, D₂O) serves as both the moderator and coolant in PHWRs.

- The heavy water moderates, or slows down, neutrons, facilitating sustained nuclear reactions.

- Fuel:

- PHWRs typically use natural uranium as fuel, consisting mostly of uranium-238 isotopes.

- Natural uranium doesn’t require enrichment processes, simplifying fuel production.

- Pressurized System:

- The reactor operates under high pressure to maintain the heavy water in a liquid state.

- High pressure prevents the heavy water from boiling, even at elevated temperatures.

- PHWRs often adhere to the CANDU (Canada Deuterium Uranium) design, a Canadian-invented technology widely used in various countries, including India.

- Advantages:

- PHWRs offer advantages like the use of natural uranium, which reduces the need for fuel enrichment.

- Heavy water’s efficiency in moderating neutrons enhances the reactor’s performance.

About Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL)

- The Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) is a public sector undertaking headquartered in Mumbai, Maharashtra.

- Established in September 1987 under the Companies Act 1956, NPCIL operates under the ownership and administration of the Government of India and falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE).

- The primary mission of NPCIL is to engage in the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of atomic power stations for electricity generation, aligning with the Government of India’s schemes and programs under the Atomic Energy Act 1962.

- NPCIL played a pivotal role in the construction and operation of India’s commercial nuclear power plants until the establishment of BHAVINI Vidyut Nigam in October 2003.

About the Department of Atomic Energy

- The Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) is an Indian government department headquartered in Mumbai, Maharashtra.

- Established in 1954 with Jawaharlal Nehru as its inaugural minister and HomiBhabha as its secretary, DAE has played a pivotal role in advancing nuclear power technology and promoting the applications of radiation across various sectors.

- Mandate and Activities:

- The primary focus of DAE is the development of nuclear power technology and the application of radiation technologies in diverse fields such as agriculture, medicine, industry, and basic research.