CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07/07/2023

India needs a Uniform Civil Code

is a former Vice President of India

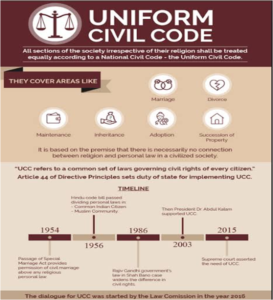

India, being a diverse nation, is home to many religions, each with its distinct personal laws governing marriage, divorce, adoption, inheritance and succession. It would be accurate to say that the absence of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) has only served to perpetuate inequalities and inconsistencies in our land of rich diversity. In fact, this has been a hindrance in the nation’s progress towards social harmony, economic and gender justice. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had last week called for the enactment of a UCC, pointing out the anomaly of having varying laws for different categories of citizens.

In the Constituent Assembly

The debate on the UCC goes back to the Constituent Assembly debates. In fact, one could assert that the legality of UCC is rooted in the Constitution of India, Constituent Assembly debates and also Supreme Court of India judgments. Constituent Assembly debates shed light on the need and the objective behind promoting a common civil code. Babasaheb Ambedkar, the chief architect of the Indian Constitution, had made a strong case in the Constituent Assembly for framing a UCC. He stressed the importance of a UCC in ensuring gender equality and eradicating prevailing social evils.

Countering the arguments of some of the members of the Constituent Assembly who were opposed to the idea, B.R. Ambedkar observed: “I personally do not understand why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field. After all, what are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is so full of inequities, so full of inequalities, discriminations and other things, which conflict with our fundamental rights. It is, therefore, quite impossible for anybody to conceive that the personal law shall be excluded from the jurisdiction of the State.”

Other distinguished and erudite members of the Constituent Assembly such as Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar and K.M. Munshi also advocated the enactment of a UCC. Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar argued that “the Article actually aims at amity….what it aims at is to try to arrive at a common measure of agreement in regard to these matters”. Similarly, K.M. Munshi also called for a UCC in the Constituent Assembly. He said: “The point however, is this, whether we are going to consolidate and unify our personal law in such a way that the way of life of the whole country may in course of time be unified and secular… What have these things got to do with religion I really fail to understand.”

Since a consensus on a UCC could not be reached in the Constituent Assembly, the subject found a place under Article 44 of the Directive Principles. Thus, Article 44, in a sense, is the Constitutional mandate which requires the state to enact a UCC that applies to all citizens cutting across faiths, practices and personal laws.

It would be also pertinent to point out here that the Supreme Court had dwelt on the matter on more than one occasion. The top court had observed in the Shah Bano case that “It is a matter of regret that Article 44 has remained a dead letter.” The Court had pointed out that a UCC would help the cause of national integration. The top court ruled that “… in the constitutional order of priorities, the right to religious freedom is to be exercised in a manner consonant with the vision underlying the provisions of Part III (Fundamental Rights)” — Indian Young Lawyers Association case (2018). However, despite articulating its views clearly on the subject in many cases, the Supreme Court refrained from issuing any clear directive to the government being mindful of the fact that the framing of laws falls within the exclusive domain of Parliament.

The essence

The UCC is, therefore, a step in the right direction, long overdue, to safeguard the fundamental rights of all citizens and reduce social inequalities and gender discrimination.

It should be seen and understood as an attempt at creating a unified legal framework that upholds the principles enshrined in the Constitution and reaffirmed by Supreme Court judgments.

The doubts in the minds of some and the opposition to this initiative stemming from unfounded apprehensions need to be addressed through enlightened debate and constructive engagement. The overarching objective is to ensure that there is no gender discrimination, everyone enjoys the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution, and that the law of the land is uniform for every citizen in our country. It will serve as a powerful instrument for the promotion of equality and justice for all citizens. Seen in this light, every citizen should welcome it.

As Babasaheb Ambedkar and other learned members of the Constituent Assembly had proposed, uniformity in personal laws is essential for empowering women and ensuring gender equality in matters of marriage, divorce, and inheritance. A UCC would eliminate discriminatory practices that deprive women of their rights and provide them with equal opportunities and protections. Our diverse society calls for a unified legal framework to foster social cohesion and national integration. The Constituent Assembly members recognised the existing challenges and stressed the need for a UCC to bridge the gaps and promote a sense of unity among diverse communities.

Personal laws should have a two-dimensional acceptance — they should be constitutionally compliant and consistent with the norms of gender equality and the right to live with dignity. The Constitution is the North Star which guides us in this regard. It exemplifies the essential principles of justice, gender equality, and secularism which, taken together, set the foundation of the UCC.

An appeal

Finally, I would like to urge my fellow citizens, leaders of religious groups and political parties to rise above all differences and support implementation of the UCC. They should contribute to making it an instrument of social reform, a legislative framework fully aligned with principles of justice and equity underscored by the Constitution, a code that provides legal protection against discrimination, a progressive piece of legislation to guarantee equal human rights and give tangible shape to the vision of the country’s illustrious founding fathers. It will be a yet another step, a very significant one, towards building a new, inclusive, egalitarian India that we all want.

The country’s progress towards social harmony, economic and gender justice has been hampered by the absence of a Uniform Civil Code.

Facts about the News

- The concept of a standard set of civil laws for all citizens of a country, regardless of religious or cultural ties, is referred to as the standard Civil Code.

- A UCC would provide for one law for the entire country, applicable to all religious communities, in their personal matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption etc.

- In other words, UCC is a set of rules/regulations, which proposes to replace the personal laws based on the scriptures and customs of each major religious community in the country with a common set governing every citizen.

Current situation in India

- Currently, Indian personal law is fairly complex, with each religion adhering to its own specific laws.

- Separate laws/ customs govern Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhist, Muslims, Christians, and followers of other religions.

- Moreover, there is diversity even within communities. All Hindus of the country are not governed by one law, nor are all Muslims or all Christians.

- For example, in the Northeast, there are more than 200 tribes with their own varied customary laws.

- The Constitution itself protects local customs in Nagaland. Similar protections are enjoyed by Meghalaya and Mizoram.

- The exception to this rule is the state of Goa, where all religions have a common law regarding marriages, divorces, and adoption.

Constitutional position

– Article 44 of the Constitution lays down that the state shall endeavour to secure a UCC for citizens throughout the territory of India.

- Article 44 is among the Directive Principles of State Policy.

- Directive Principles are not enforceable by court, but are supposed to inform and guide governance.

Please read- Shah Bano judgement

Stand of the 21st Law Commission on the matter

- In 2018, 21st Law Commission underlined that the Uniform Civil Code is neither necessary nor desirable at this stage.

- It argued for reform of family laws of every religion through amendments and codification of certain aspects so as to make them gender-just.

- It further said that cultural diversity cannot be compromised to the extent that our urge for uniformity itself becomes a reason for threat to the territorial integrity of the nation.

Need for UCC

- To promote national unity

- Different personal laws are put to subversive use

- Gender justice and Equality

- Not in the domain of religious activities

- Simplification and Rationalization of legal system

- Vision of constitution makers

Arguments against UCC

- Diversity cannot be compromised for uniformity

- Violation of fundamental rights

- Constitution recognises the customary laws and procedures prevailing in NE states

- Detrimental to communal harmony of India

SC Related Cases

| Landmark Cases | Ruling and Implications |

| Shah Bano Case (1985) | The Supreme Court upheld the right of a Muslim woman to claim maintenance from her husband even after the Iddat period. |

| It highlighted the need for a UCC to remove contradictions based on ideologies. | |

| Sarla Mudgal (1995) | The Supreme Court stated that a Hindu husband cannot convert to Islam and marry without dissolving his first marriage. |

| It emphasized that a UCC would prevent fraudulent conversions and bigamous marriages. | |

| Shayara Bano case (2017) | The Supreme Court declared triple talaq as unconstitutional and violative of Muslim women’s dignity and equality. |

| It recommended that Parliament enact a law to regulate Muslim marriages and divorces. |

Internationalising the rupee without the ‘coin tossing’

is a third term Member of Parliament (BJP), representing the parliamentary constituency of Pilibhit in Uttar Pradesh

The government’s announcement of a long-term road map for further internationalisation of the rupee can turn out to be a positive exercise. In the 1950s, the Indian rupee was legal tender for almost all transactions in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman and Qatar, with the Gulf monarchies purchasing rupees with the pound sterling. In 1959, to mitigate challenges associated with gold smuggling, the Reserve Bank of India (Amendment) Act was brought in, enabling the creation of the “Gulf Rupee”, with notes issued by the central bank for circulation only in the West Asian region. Holders of the Indian currency were given six weeks to exchange their Indian currency, with the transition happening smoothly. However, by 1966, India devalued its currency, eventually causing some West Asian countries to replace the Gulf rupee with their own currencies. Flagging confidence in the Indian rupee’s stability combined with an oil-revenue linked boom, slowly led to the introduction of sovereign currencies in the region. The move, in 2023, to withdraw the ₹2,000 note has also impacted confidence in the rupee.

The demonetisation of 2016 also shook confidence in the Indian rupee, especially in Bhutan and Nepal. Both countries continue to fear additional policy changes by the RBI (including further demonetisation). The rupee’s internationalisation cannot make a start without accounting for the concerns expressed by India’s neighbours.

Very little international demand

The rupee is far from being internationalised — the daily average share for the rupee in the global foreign exchange market hovers around ~1.6%, while India’s share of global goods trade is ~2%. India has taken some steps to promote the internationalisation of the rupee (e.g., enable external commercial borrowings in rupees), with a push to Indian banks to open Rupee Vostro accounts for banks from Russia, the UAE, Sri Lanka and Mauritius and measures to trade with ~18 countries in rupees instituted. However, such transactions have been limited, with India still buying oil from Russia in dollars. Ongoing negotiations with Russia to settle trade in rupees have been slow-going, with Russia expected to have an annual rupee surplus of over $40 billion — reports indicate that Russian banks have been averse to the trade, given the risk of further currency depreciation and a lack of awareness among traders about local currency facilities. In short, there is very little international demand to trade in the Indian rupee.

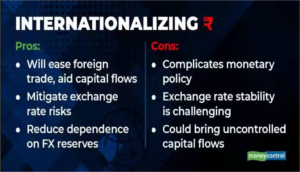

For a currency to be considered a reserve currency, the rupee needs to be fully convertible, readily usable, and available in sufficient quantities. India does not permit full capital account convertibility (i.e., allowing free movement of local financial investment assets into foreign assets and vice-versa), with significant constraints on the exchange of its currency with others — driven by past fears of capital flight (i.e., outflow of capital from India due to monetary policies/lack of growth) and exchange rate volatility, given significant current and capital account deficits.

China’s experience

China’s example in internationalising the Renminbi has lessons. As an online article highlights, before 2004, the RMB could not be used outside China. By 2007, the “Dim Sum” bond and offshore RMBD bond market had been created, with financial institutions in Hong Kong allowed to issue dim sum bonds by 2009. Post 2008, China pursued a phased approach, enabling the use of the RMB for trade finance (i.e., financial instruments for facilitating international trade and commerce), investment and, over the long term, as a reserve currency.

First, it allowed the use of RMB outside China for current account transactions (e.g., commercial trade, interest payment, dividend payments) and for select investment transactions (e.g., foreign direct investment, outward direct investment). By 2009, China had signed currency swap agreements (i.e., an exchange of an equivalent amount of money, but in different currencies) with countries such as Brazil, the United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, and Thailand. Soon, it allowed central banks, offshore clearing banks and offshore participating banks to invest excess RMB in debt securities. The Shanghai Free Trade Zone was launched in September 2013, to allow free trading between non-resident onshore and offshore accounts.

Over time, the RMB was internationalised, with reserve currency status increasingly enabled (e.g., by Q2 2022, the RMB’s share of international reserves had reached ~2.88%), as the article highlights.

Pursue these reforms

Many reforms can be pursued to internationalise the rupee. It must be made more freely convertible, with a goal of full convertibility by 2060 – letting financial investments move freely between India and abroad. This would allow foreign investors to easily buy and sell the rupee, enhancing its liquidity and making it more attractive. Additionally, the RBI should pursue a deeper and more liquid rupee bond market, enabling foreign investors and Indian trade partners to have more investment options in rupees, enabling its international use. Indian exporters and importers should be encouraged to invoice their transactions in rupee — optimising the trade settlement formalities for rupee import/export transactions would go a long way. Additional currency swap agreements (as with Sri Lanka) would further allow India to settle trade and investment transactions in rupees, without resorting to a reserve currency such as the dollar.

Additionally, tax incentives to foreign businesses to utilise the rupee in operations in India would also help. The RBI and the Ministry of Finance must ensure currency management stability (consistent and predictable issuance/retrieval of notes and coins) and improve the exchange rate regime. More demonetisation (or devaluation) will impact confidence. A start could be made to push for making the rupee an official currency in international organisations, thereby giving it a higher profile and acceptability. The Tarapore Committees’ (in 1997 and 2006) recommendations must be pursued including a push to reduce fiscal deficits lower than 3.5%, a reduction in gross inflation rate to 3%-5%, and a reduction in gross banking non-performing assets to less than 5%.

The government’s road map for further internationalisation of the rupee will make it easier for Indian businesses to do business/invest abroad and enhance the rupee’s liquidity, while enhancing financial stability. It must also benefit Indian citizens, enterprises and the government’s ability to finance deficits. It is a delicate balance to trade off rupee convertibility for exchange rate stability. One hopes predictable currency management policies will be instituted.

India must pursue reforms confidently to internationalise the rupee, which will result in a number of benefits.

Facts about the News

Internationalisation is a process that involves increasing the use of the rupee in cross-border transactions.

It involves promoting the rupee for import and export trade and then other current account transactions, followed by its use in capital account transactions. These are all transactions between residents in India and non-residents. The internationalisation of the currency, which is closely interlinked with the nation’s economic progress, requires further opening up of the currency settlement and a strong swap and forex market.

Understanding dark patterns

EXPLAINER

The Department of Consumer Affairs and the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) recently held a joint consultation with stakeholders on the menace of ‘dark patterns’. The ASCI has come up with guidelines for the same, with the central government also working towards norms against ‘dark patterns’.

What are dark patterns?

Harry Brignull, a user experience researcher in the U.K., introduced the phrase ‘dark pattern’ in 2010 to characterise deceptive strategies used to trick clients. A dark pattern refers to a design or user interface technique that is intentionally crafted to manipulate or deceive users into making certain choices or taking specific actions that may not be in their best interest. It is a deceptive practice employed to influence user behaviour in a way that benefits the company implementing it.

For example, a common dark pattern is the “sneak into basket” technique used on e-commerce websites. When a user adds an item to their shopping cart, a dark pattern may be employed by automatically adding additional items to the cart without the user’s explicit consent or clear notification. This can mislead the user into purchasing more items than they intended, potentially increasing the company’s sales but compromising the user’s autonomy and decision-making. Similarly, many of us have encountered pop-up requests for our personal information, where we have found it difficult to locate the ‘reject’ link. It is challenging for customers to decline the acquisition of their personal data if they want to continue on a website because the choice to depart or reject is so subtly positioned. By using such dark patterns, digital platforms infringe on the consumer’s right to full transparency of the services they use and control over their browsing experience.

What are the different types?

Businesses are using various techniques and deceptive patterns to downgrade the user experience to their own advantage. Some of the common practices are — creating a sense of urgency or scarcity while online shopping; confirm shaming wherein a consumer is criticised for not conforming to a particular belief; the forced action of signing up for a service to access content; advertising one product or service but delivering another, often of lower quality, known as the bait and switch technique; hidden costs where the bill is revised or costs are added when the consumer is almost certain to purchase the product; disguised advertisements of a particular product by way of depicting it as news and many more. Such deceptive patterns that manipulate consumer choice and impede their right to be well-informed constitute unfair practices that are prohibited under the Consumer Protection Act 2019.

Are dark patterns illegal?

Many believe that the use of dark patterns is a business strategy. The legality of dark patterns is a complex matter as distinguishing between manipulation and fraudulent intent can be challenging. As of now, there are no specific regulations in place in most nations against dark patterns. Nonetheless, individuals who have experienced harm as a result of dark patterns may potentially seek compensation for damages. In 2022, Google and Facebook faced repercussions due to their cookie banners. These companies violated EU and French regulations by making it more difficult for users to reject cookies as compared to accepting them.

What are global regulators saying?

Major international authorities are acting and formulating rules to address the issue. In a letter to U.K. businesses, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) of the U.K. lists different pressure-selling techniques that the CMA believes would likely violate consumer protection laws and for which actions will be taken. Guidelines from the European Data Protection Board were released in 2022 and offered designers and users of social media platforms practical guidance on how to spot and avoid so-called “dark patterns” in social media interfaces that are in violation of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) laws.

How do we address dark patterns?

The Department of Consumer Affairs and the ASCI have identified the issue and recently taken certain steps to handle the same. As of now, companies are being asked to desist from using such tactics in the e-market and on June 30, 2023, as per information by the PIB, major Indian online marketplaces received a letter from the Department of Consumer Affairs warning them against engaging in “unfair trade practices” by implementing “dark patterns” in their user interfaces to influence consumer choice and infringe on “consumer rights” as stated in Section 2(9) of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019. However, with the growing use of e- platforms, a robust legal mechanism is a demand. The Indian government should also amend existing laws to specifically address dark patterns. To do this, new rules aimed against deceptive design practices may need to be introduced along with updated consumer protection laws and data protection legislation.

G. S. Bajpai is Vice Chancellor, National Law University Delhi and Ankit serves as Assistant Professor at RGNUL, Punjab.

THE GIST

A dark pattern refers to a design or user interface technique that is intentionally crafted to manipulate or deceive users into making certain choices or taking specific actions that may not be in their best interest.

Many believe that the use of dark patterns is a business strategy. The legality of dark patterns is a complex matter as distinguishing between manipulation and fraudulent intent can be challenging.

On June 30, 2023, as per information by the PIB, major Indian online marketplaces received a letter from the Department of Consumer Affairs warning them against engaging in “unfair trade practices” by implementing “dark patterns” in their user interfaces to influence consumer choice.

Facts about the News

Dark patterns, also known as deceptive patterns, is a term used to describe ways or tricks implemented by websites or apps to make users do things that they didn’t intend to, or discourage behaviour that’s not beneficial for companies.

The term dark patterns was coined by Harry Brignull, a London-based user experience (UX) designer, in 2010.

Think of that annoying advertisement that keeps popping up on your screen, and you can’t find the cross mark ‘X’ to make it go away because the mark is too small to notice (or to click/ tap). Worse, when you try to click/ tap on the tiny ‘X’, you sometimes end up tapping the ad instead.

For example Instagram allows users to deactivate their account through the app, but they must visit the website if they want to delete the account.

The Consumer Affairs Ministry has identified nine types of dark patterns being used by e-commerce companies. Most of these are also listed on deceptive design.

* False urgency: Creates a sense of urgency or scarcity to pressure consumers into making a purchase or taking an action;

* Basket sneaking: Dark patterns are used to add additional products or services to the shopping cart without the user’s consent;

* Confirm shaming: Uses guilt to make consumers adhere; criticises or attacks consumers for not conforming to a particular belief or viewpoint;

* Forced action: Pushes consumers into taking an action they may not want to take, such as signing up for a service in order to access content;

* Nagging: Persistent criticism, complaints, and requests for action;

* Subscription traps: Easy to sign up for a service but difficult to quit or cancel; option is hidden or requires multiple steps;

* Bait & switch: Advertising a certain product/ service but delivering another, often of lower quality;

* Hidden costs: Hiding additional costs until consumers are already committed to making a purchase;

* Disguised ads: Designed to look like content, such as news articles or user-generated content.

Global Laws Against Dark Patterns: Several governments across the globe have defined ‘dark patterns’ and brought in strict laws against them.

US: In the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission [FTC] has taken note of dark patterns and the risks they pose. In a report released in September 2022 year, the regulatory body listed over 30 dark patterns, many of which are considered standard practice across social media platforms and e-commerce sites. FTC report outlined its legal action against Amazon in 2014, for a supposedly “free” children’s app that fooled its young users into making in-app purchases that their parents had to pay for.

EU: The European Union has enacted Digital Services Act (DSA) to curb the menace of dark pattern and create a safer digital space in which the fundamental rights of all users of digital services are protected. DSA regulates digital services that act as “intermediaries” in their role of connecting consumers with content, goods and services. This means not only are the likes of Facebook and Google within the scope of the bill, but also Amazon and app stores. Violations carry the threat of a fine of 6% of global turnover and, in the most serious cases, a temporary suspension of the service.

Regulatory Framework in India:

Consumer Protection Act 2019:

- Deceptive patterns that manipulate consumer choice and impede their right to be well informed constitute unfair practices that are prohibited under the Consumer Protection Act 2019.

Department of Consumer Affairs (DoCA):

- It is one of the two Departments under the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution. Implementation of Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI):

- It is an independent, voluntary self-regulatory organization formed in 1985 by professionals from the advertising and media industry to keep Indian ads decent.

- It aims to ensure advertisements in India are fair, honest and are compliant with the ASCI Code

Why there is a Need to Regulate Dark Patterns in India? 250 words

What are the provisions of the High Seas Treaty?

Why did some developed countries oppose the treaty? What were some of the most contentious issues in the Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction treaty?

The story so far:

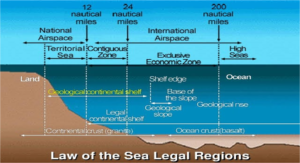

On June 19, the UN adopted the Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) or the High Seas Treaty. It became the third agreement to be approved under UNCLOS, after the 1994 and 1995 treaties, which established the International Seabed Authority and the Fish Stocks agreement.

When did the process start?

The idea of protecting the marine environment emerged in 2002. By 2008, the need for implementing an agreement was recognised, which led to the UNGA resolution in 2015 to form a Preparatory Committee to create the treaty. The Committee recommended the holding of intergovernmental conferences (IGC) and after five prolonged IGC negotiations, the treaty was adopted in 2023. The treaty’s objective is to implement international regulations to protect life in oceans beyond national jurisdiction through international cooperation.

What does the treaty entail?

The treaty aims to address critical issues such as the increasing sea surface temperatures, overexploitation of marine biodiversity, overfishing, coastal pollution, and unsustainable practices beyond national jurisdiction. The first step is establishing marine protected areas to protect oceans from human activities through a “three-quarterly majority vote,” which prevents the decision from getting blocked by one or two parties. On the fair sharing of benefits from marine genetic resources, the treaty mandates sharing of scientific information and monetary benefits through installing a “clear house mechanism.” Through the mechanism, information on marine protected areas, marine genetic resources, and “area-based management tools” will be open to access for all parties. This is to bring transparency and boost cooperation. The last pillar of the treaty is capacity building and marine technology. The Scientific and Technical Body will also play a significant role in environmental impact assessment. The body will be creating standards and guidelines for assessment procedures, and helping countries with less capacity in carrying out assessments. This will facilitate the conference of parties to trace future impacts, identify data gaps, and bring out research priorities.

Why did it take so long to sign?

The marine genetic resources issue was the treaty’s most contended element. The parties to the treaty must share and exchange information on marine protected areas and technical, scientific and area-based management tools to ensure open access of knowledge. The negotiations on the subject were prolonged due to the absence of a provision to monitor information sharing. In IGC-2, small island states supported the idea of having a licensing scheme for monitoring, but was opposed by the likes of the U.S., and Russia, stating its notification system would hinder “bioprospecting research.”

Another debate was over definition. The use of the phrases “promote” or “ensure” in different parts of the treaty, especially with respect to the sharing of benefits from marine genetic resources, was heavily debated over. And finally, there was the prolonged negotiation over the adjacency issue. This was specifically applicable to coastal states whose national jurisdictions over the seas may vary. This meant it required special provisions where it can exercise sovereign rights over seabed and subsoil in the jurisdiction beyond. It prolonged the decision-making as it affects the interests of landlocked and distant states.

Who opposed the treaty?

Many developed countries opposed the treaty as they stand by private entities which are at the forefront of advanced research and development in marine technology (patents relating to marine genetic resources are held by a small group of private companies). Russia and China also are not in favour of the treaty. Russia withdrew from the last stage of reaching a consensus in IGC-5, arguing that the treaty does not balance conservation and sustainability.

Padmashree Anandhan is a Research Associate at NIAS, Bengaluru

THE GIST

On June 19, the UN adopted the Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) or the High Seas Treaty.

The treaty aims to address critical issues such as the increasing sea surface temperatures, overexploitation of marine biodiversity, overfishing, coastal pollution, and unsustainable practices beyond national jurisdiction.

Many developed countries opposed the treaty as they stand by private entities which are at the forefront of advanced research and development in marine technology.

FinMin pushes for reforms to spur FDI

The Finance Ministry has made a strong pitch for measures to facilitate Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows, that dipped last year and may remain subdued in the coming months. It mooted greater attention from policymakers to resolve challenges faced by global investors, including last-mile infrastructure issues and difficulties in setting up large-scale factories.

Blaming the dip in FDI inflows in FY23 to inflationary pressures and tighter monetary policies, the Ministry noted that FDI flows may also be impacted by “political distance more than geographical distance” as “geopolitics has dominated geography.”

‘Not unique to India’

Gross FDI flows slid 16% last year from the record high of $84.8 billion in FY22, while net inflows fell a sharper 27.4%. In its annual economic review published on Thursday, the Ministry said this phenomenon was “not unique to India” as net FDI inflows to emerging market economies declined 36% in 2022.

Identifying the external sector as a possible challenge for India’s growth outlook in FY24, the Ministry noted that “escalation of geopolitical stress, enhanced volatility in global financial systems, sharp price correction in global stock markets, a high magnitude of El-Nino impact, and modest trade activity and FDI inflows owing to frail global demand” could all constrain growth.

“India needs to watch FDI data closely and continue to take measures to facilitate FDI inflows. Last-mile infrastructure issues, labour availability and measures to facilitate large capacity creation will be needed. This policy space may need India’s increasing attention in the coming months and years,” it said.

“Friend shoring” of FDI by increasing investments in countries which are geopolitically aligned to each other was leading to a fragmentation in FDI flows across the globe, the Ministry noted, citing research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Inflows from foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) into the Indian markets had become less volatile, it asserted.

On the trade front, the Ministry identified the European Union’s introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), for which carbon content reporting will be mandatory from October 1, as an impending downside risk to India’s exports.

‘Rising inclusivity’

Countering criticism about an uneven recovery, the Ministry said that job creation played a key role in boosting demand in the economy from FY21 to FY23. So, “it bespeaks the rising inclusivity in the growth of the Indian economy,” it contended.

“Going forward, employment levels are expected to remain buoyant, mainly driven by rapid digitalisation, technological advancement, and the expanding implementation of the PLI [production-linked incentive] scheme, thereby creating employment avenues for both semi-skilled and skilled workers,” the Ministry underlined in its review.

Facts about the News

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a type of cross-border investment in which an investor from one country establishes a lasting interest in an enterprise in another country.

- FDI can take various forms, such as acquiring shares, establishing a subsidiary or a joint venture, or providing loans or technology transfers.

- FDI is considered to be a key driver of economic growth, as it can bring in capital, technology, skills, market access and employment opportunities to the host country.

SOURCE : THE HINDU