CURRENT AFFAIRS – 05/04/2024

CURRENT AFFAIRS – 05/04/2024

Govt. to record parents’ religion to register births

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

The Union Ministry of Home Affairs has drafted Model Rules altering the birth registration process in India.

- These changes mandate the recording of the religion of both parents during registration, a departure from the previous practice of solely noting the family’s religion.

Key Highlights

- Inclusion of Parental Religion in Birth Records:

- Under the proposed “Form No.1-Birth Report,” parents registering a child’s birth must now specify the religion of both the father and mother, alongside the child’s religion.

- This expanded documentation also applies to parents of adopted children, reflecting a comprehensive approach to demographic data collection.

- Legislative Background:

- The Registration of Births and Deaths (Amendment) Act, 2023, enacted on August 11 the preceding year, forms the legal basis for these changes.

- This Act facilitates the maintenance of a national birth and death database, which may integrate with various governmental databases, including the National Population Register (NPR), electoral rolls, and Aadhaar.

- Digitization of Birth Records:

- Since October 1 of the same year, all births and deaths in the country are digitally registered through the Civil Registration System portal (crsorgi.gov.in).

- This digitization initiative aims to streamline administrative processes and ensure accuracy in record-keeping.

- Furthermore, digital birth certificates issued through this system serve as authoritative documents for verifying individuals’ dates of birth, crucial for accessing services like educational institutions.

- Proposed Form Revisions:

- The Registrar General of India (RGI) within the Ministry of Home Affairs suggests substituting existing registration forms with revised versions.

- These include forms for births, deaths, still births, adoptions, and the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD).

- Notably, the MCCD will now require additional information, such as the deceased’s medical history, in addition to the primary cause of death.

- Legal and Statistical Information in Birth Registers:

- Birth registers typically contain two sections: legal information and statistical information.

- The legal information section of birth register forms has been enhanced to include additional details.

- These additions encompass the Aadhaar numbers, mobile numbers, and email addresses of both parents, provided they are available.

- Moreover, the address field has been elaborated to encompass various geographical identifiers such as State, district, sub-district, town or village, ward number (if applicable), locality, house number, and PIN code.

- Requirements for Informants:

- The individual providing the birth information, known as the informant, is now obligated to furnish their own Aadhaar number, mobile number, and email address.

- Previously, only their name and address details were required.

- Maintenance of National Database:

- Per the 2023 amendment, the Registrar General of India (RGI) is tasked with maintaining a national database of registered births and deaths.

- It is mandatory for Chief Registrars and Registrars, appointed by State governments, to share data of registered births and deaths with this central database.

- Under the parent Act, the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969, the RGI holds authority to coordinate and unify the activities of Chief Registrars appointed by State governments.

- The Civil Registration System (CRS) extends its functionaries down to the panchayat level, ensuring comprehensive coverage.

- Utilization of CRS Data:

- Data collected through the CRS is utilized to compile the annual ‘Vital Statistics of India Based on the Civil Registration System’ report.

- This report provides insights into vital demographic indicators such as sex ratio at birth, infant mortality, stillbirths, and deaths at the national level.

- Such data is instrumental in informing socio-economic planning, evaluating the efficacy of social sector programs, and forming the foundation of the public health system in the country.

About the Registrar General of India (RGI)

- The Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India (RGI) is a government agency responsible for arranging, conducting, and analyzing the results of demographic surveys in India, including the Census of India and the Linguistic Survey of India.

- The RGI is a permanent department of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, and is headed by a civil servant holding the rank of Joint Secretary.

- The RGI is responsible for the following:

- Housing & Population Census:

- The RGI is the statutory authority responsible for conducting the Housing and Population Census in India under the Census Act, 1948, and Rules framed thereunder.

- National Population Register (NPR):

- The RGI is responsible for preparing the National Population Register (NPR) by collecting information relating to all persons who are usually residing in the country.

- Civil Registration System (CRS):

- The RGI is designated as the Registrar General, India, under the Registration of Births & Deaths Act, 1969, which provides for the compulsory registration of births and deaths.

- Sample Registration System (SRS):

- The RGI is responsible for implementing the Sample Registration System, wherein large scale sample survey of vital events is conducted on a half-yearly basis.

- SRS is an important source of vital rates like Birth Rate, Death Rate, Infant Mortality Rate, and Maternal Mortality Rate at the State level in the country.

- Mother Tongue Survey:

- The RGI conducts a project that surveys the mother tongues, which are returned consistently across two and more Census decades.

- The research programme documents the linguistic features of the selected mother tongues.

- Linguistic Survey:

- The RGI conducts a Linguistic Survey of India (LSI) as a regular research activity since the 6thFive Year Plan.

- The RGI has a long tradition of having regular decennial Population Censuses since 1872.

- The last Population Census was conducted in 2011, and the next decennial Census is to be conducted in 2021, which will be the 16th Census in the continuous series from 1872 and 8th Census since independence.

- Housing & Population Census:

Revisit these sections of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

The central government has officially announced July 1, 2024, as the commencement date for three recently enacted criminal laws.

- Section 106(2) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, which mandates a maximum imprisonment of 10 years for fleeing the scene of a fatal accident without reporting to authorities, has been temporarily suspended.

- This decision was prompted by concerns raised by the All India Motor Transport Congress, following a strike by truck drivers who deemed the provision excessively severe.

Key Highlights

- Pending Discussions and Reconsideration:

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) issued a press statement on January 2, indicating that the decision regarding the implementation of Section 106(2) would be made after consultations with the All India Motor Transport Congress.

- Additionally, it is deemed pertinent for the central government to reassess several other provisions of the BNS, including those related to “petty organized crime” defined under Section 112, “theft” defined under Section 303(2), and specific sub-sections of Section 143 concerning human trafficking.

- Significance of Reconsidering Section 106(2):

- The proposed increase in sentence duration, from five to 10 years of imprisonment for fleeing the accident scene without immediately reporting to authorities, is viewed as disproportionate.

- Unlike other legal provisions, this clause doesn’t address the immediate need for medical assistance to potentially injured individuals but focuses solely on reporting the accident.

- However, it’s noted that the provision facilitates seeking appropriate motor accident claims if vehicle details are known.

- Constitutional Concerns:

- There are constitutional implications regarding Section 106(2), particularly concerning Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India, which safeguards against self-incrimination.

- The clause potentially conflicts with this fundamental right, as it might compel individuals to disclose culpability out of fear of enhanced punishment.

- The Supreme Court of India, in NandiniSatpathy vs P.L. Dani, has broadened the interpretation of Article 20(3) to encompass various forms of coercion beyond physical threats, including psychological pressure.

- Therefore, the requirement to inform authorities due to the fear of increased penalties may not align with constitutional principles.

- Introduction of ‘Petty Organised Crime’ Offence:

- Section 112 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) introduces a novel offense termed as ‘petty organized crime.’

- This offense applies to individuals who, as part of a group or gang, engage in various criminal activities such as theft, snatching, cheating, unauthorized selling of tickets, unauthorized betting or gambling, selling of public examination question papers, or similar criminal acts.

- Ambiguities in Definition and Classification:

- Certain offenses mentioned, like “unauthorized selling of tickets” and “selling of public examination question papers,” lack specific legal definitions within the BNS or other special acts.

- The phrase “any other similar criminal acts” in the section adds further ambiguity.

- Notably, while theft and snatching carry penalties of up to three years imprisonment (Section 303 of the BNS), theft in specific circumstances can entail up to seven or ten years of imprisonment (Sections 305 and 307 of the BNS, respectively).

- Similarly, cheating provisions prescribe sentences ranging from three to seven years (Section 318 of the BNS).

- Unspecified Scope and Legal Scrutiny:

- The phrase “any other similar criminal acts” leaves the scope of the offense undefined, potentially encompassing offenses like criminal breach of trust, misappropriation of property, and receiving stolen goods.

- However, the sentences for these offenses vary, some even reaching up to ten years.

- This discrepancy raises concerns regarding the classification of offenses as “petty,” especially when certain offenses carry sentences exceeding the maximum specified for petty organized crime.

- Challenges for Legal Validity:

- Without specific limits on sentence duration, the provision may face scrutiny from the Supreme Court.

- The comparison is drawn with the striking down of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, by the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal vs Union of India (2015).

- The court deemed the term “grossly offensive” in Section 66A as undefined and vague, leading to its nullification.

- Similarly, the ambiguity surrounding ‘petty organized crime’ raises questions about its legal validity and potential challenge before the judiciary.

- Revisiting Theft Offense Provisions:

- The theft offense, as outlined in the proviso to Sub-section (2) of Section 303 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), warrants reconsideration.

- This provision addresses cases where the value of stolen property is less than ₹5,000 and a person is convicted for the first time.

- In such instances, community service is prescribed upon the return or restoration of the stolen property.

- Impact on Vulnerable Individuals:

- While designating theft of property valued under ₹5,000 as a non-cognizable offense may alleviate the police workload, it presents challenges both legally and practically.

- The monetary threshold may seem inconsequential to wealthier individuals in urban areas but could significantly affect individuals with limited financial means.

- For instance, a student whose bicycle is stolen may face hurdles if the police refuse to file a first information report due to the non-cognizable nature of the case.

- This disparity in access to justice could leave vulnerable individuals feeling helpless, particularly those reliant on government-provided bicycles for education.

- Non-registration of property offenses below the ₹5,000 threshold could remove property offenders from police surveillance unless they engage in other cognizable offenses.

- Legal complexities may arise concerning the return of such property if recovered alongside other stolen items.

- Additionally, failure to return or restore stolen property under this provision could lead to imprisonment for up to three years, akin to penalties for higher-value thefts.

- Addressing Interplay Between Sub-sections:

- While tweaking definitions and prescribing alternate punishments for cases where stolen property isn’t returned or restored could mitigate confusion, a broader solution is proposed.

- Designating theft of property of any value as a cognizable offense, requiring only minor adjustments to the First Schedule of the BharatiyaNagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), could address various legal and practical concerns.

- This approach would eliminate disparities in treatment based on property value, ensuring equitable access to justice and enhancing police surveillance capabilities.

- Revisiting Legal Provisions in the BNS:

- Section 303 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which dealt with the punishment for murder by a life-convict, was deemed void and unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the case of Mithu vs State of Punjab (1983).

- One of the key reasons cited for its unconstitutionality was the lack of discretion granted to the judiciary, rendering the law unjust, unfair, and unreasonable under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- Restoration in the BNS:

- Section 303 of the IPC has been reintroduced in the form of Section 104 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), addressing the concerns that led to its previous nullification.

- Section 104 of the BNS now offers the option of either death penalty or imprisonment for life, implying imprisonment for the remainder of the convict’s natural life.

- Similar Issues in Other BNS Provisions:

- Despite the rectification made to Section 303, certain provisions in the BNS still raise legal and constitutional concerns.

- Specifically, Sub-sections (6) and (7) of Section 143, which pertain to trafficking offenses, impose mandatory life imprisonment without granting any discretion to the judiciary in sentencing.

- This lack of judicial discretion mirrors the flaw identified in the invalidated Section 303 of the IPC.

- Need for Reassessment:

- Sub-section (2) of Section 106, Section 112, Sub-section (2) of Section 303, and Sub-sections (6) and (7) of Section 143 of the BNS exhibit potential legal and/or constitutional issues due to the absence of judicial discretion in sentencing.

- This deficiency undermines the principles of justice and fairness enshrined in the Constitution.

- Furthermore, these provisions may have practical repercussions, as they limit the judiciary’s ability to tailor punishments to the circumstances of individual cases.

- Mandatory sentencing without judicial discretion could lead to disproportionate or unjust outcomes in certain situations.

About the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023

- The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) is a comprehensive legal framework introduced in India in 2023 to replace the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860.

- The BNS is designed to be in tune with society’s evolving needs and commitment to justice.

- It is subdivided into twenty chapters, comprising three hundred and fifty-eight sections.

- The BNS largely retains the provisions of the IPC, adds some new offences, removes offences that have been struck down by courts, and increases penalties for several offences.

- It covers offences affecting human body, property, public order, public health, safety, decency, morality, religion, defamation, and offences against the state.

- Key Changes:

- The BNS introduces community service as a form of punishment for certain offences such as public servant non-appearance in response to a proclamation under the BharatiyaNagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, attempt to commit suicide to compel or restrain exercise of lawful power, misconduct in public by a drunken person, and defamation.

- The BNS also removes the offence of sedition and instead penalises the following:

- (i) exciting or attempting to excite secession, armed rebellion, or subversive activities,

- (ii) encouraging feelings of separatist activities, or

- (iii) endangering the sovereignty or unity and integrity of India.

- The BNS adds terrorism as an offence, defined as an act that intends to threaten the unity, integrity, security or economic security of the country, or strike terror in the people.

- Organised crime has also been added as an offence, including crimes such as kidnapping, extortion, and cyber-crime committed on behalf of a crime syndicate.

- The BNS changes the provision of protection from prosecution to a person of unsound mind to a person with mental illness, defined as mental retardation and includes abuse of alcohol and drugs.

- The age of criminal responsibility is retained at seven years, extending to 12 years depending upon the maturity of the accused.

- The BNS omits S. 377 of IPC which was read down by the Supreme Court, removing rape of men and bestiality as offences.

- However, it retains the provisions of the IPC on rape and sexual harassment, and does not consider recommendations of the Justice Verma Committee (2013) such as making the offence of rape gender neutral.

- The BNS also defines a child to mean a person below the age of 18, but for several offences, the age threshold of the victim for offences against children is not 18.

- The threshold for minority of the victim of for rape and gangrape is different.

- The BNS removes sedition as an offence, but the provision on endangering the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India may have retained aspects of sedition.

- The BNS was introduced on August 11, 2023, and was examined by the Standing Committee on Home Affairs.

- The Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita, 2023 (BNS2) was introduced on December 12, 2023, after the earlier Bill was withdrawn, incorporating certain recommendations of the Standing Committee.

- The BNS2 largely retains the provisions of the IPC, adds some new offences, removes offences that have been struck down by courts, and increases penalties for several offences.

Overkill: On only a 100% recount of VVPATs

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

Despite the introduction of the Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) as an adjunct system to Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) and the provision for counting VVPAT tallies from five random polling booths in every Assembly constituency, critics remain skeptical about the use of EVMs in Indian elections.

Key Highlights

- Calls for Enhanced Transparency:

- Some critics suggest that maintaining a machine audit trail of all executed commands beyond just recording votes in the EVM’s ballot unit and the printed slips in VVPATs could enhance transparency.

- This proposal aims to rule out any potential malicious code, potentially making the system more robust and considered an upgrade to existing machines.

- Others argue that the introduction of VVPATs has introduced potential vulnerabilities that did not exist with standalone EVMs, necessitating a reworking of safeguards to ensure the security and reliability of combined systems.

- Many, including political parties like the Congress, insist that only a 100% recount of all VVPATs would ensure full transparency, challenging the current method of sampling recounts.

- The Supreme Court of India has listed a series of petitions related to this demand.

- Lack of Evidence of Malpractice:

- Despite concerns and allegations of malpractice and EVM hacking, there has been no concrete proof of tampering with EVMs to date.

- Glitches have occurred, but they have been promptly addressed by replacing malfunctioning machines.

- Data from sample counting of VVPATs during elections, including the general election in 2019 and various Assembly elections, indicates minuscule mismatches between VVPAT recounts and EVM counts.

- These discrepancies are often attributed to minor errors such as failure to delete mock polls before voting or errors in manual recording.

- Proposed Solutions and Trust in EVMs:

- Suggestions include increasing the recount sample to ensure statistical significance, possibly by tailoring the number of Assemblies selected for recount based on the size of the province or by increasing the recount sample in seats with narrow victory margins.

- Insisting on a full recount is deemed excessive and indicative of a lack of trust in the EVM system itself.

- It is argued that measures like enhanced recount sampling could address concerns without resorting to such extreme measures.

About the Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs)

- Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) are electronic devices used for casting and counting votes in India.

- Background:

- The Electronic Voting Machine (EVM) was conceived in 1977 by the Election Commission of India, and the task of designing and developing it was assigned to the Electronics Corporation of India Ltd. (ECIL) in Hyderabad.

- By 1979, a prototype was developed, and it was demonstrated to political party representatives in 1980.

- Bharat Electronics Ltd. (BEL) in Bangalore was later enlisted to manufacture EVMs alongside ECIL.

- The first use of EVMs occurred in the general election in Kerala in May 1982, but without specific legal backing, the election was invalidated by the Supreme Court.

- In 1989, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 was amended by Parliament to include provisions for the use of EVMs in elections.

- However, it wasn’t until 1998 that a broad consensus was reached, leading to the use of EVMs in 25 Legislative Assembly constituencies across Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Delhi.

- After preliminary success, the technology was then rolled out in a phased manner for subsequent assembly elections.

- EVMs replaced paper ballots throughout the country from 2001 onwards.

- An EVM consists of two units: a ballot unit and a control unit.

- The ballot unit is the one which is placed inside the polling booth, and the voter casts his vote by pressing the button against the name of the candidate.

- The control unit is connected to the ballot unit and is placed with the polling officer.

- It controls the functioning of the ballot unit and stores the votes cast.

- The EVMs have several advantages over the traditional paper ballot system.

- They reduce the time required for counting of votes, thereby reducing the time required for the declaration of results.

- They also eliminate the possibility of invalid votes, as the voter has to press the button against the name of the candidate.

- They also reduce the cost of elections, as there is no need for printing of ballot papers.

- The EVMs have undergone several technological changes over the years.

- The pre-2006 era EVMs are known as ‘M1 EVMs’, while those manufactured between 2006 to 2010 are called ‘M2 EVMs’.

- The latest generation of EVMs, produced since 2013, are known as ‘M3 EVMs’.

- To improve the transparency and verifiability in the poll process, the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961 were amended in 2013 to introduce the use of Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machines.

- They were first used in the by-election for the Noksen assembly seat in Nagaland.

Universities must budge on college autonomy nudge

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

The National Education Policy 2020 envisages a future where colleges transition into autonomous institutions, emphasizing innovation, self-governance, and academic freedom.

- In alignment with this vision, the University Grants Commission (UGC) introduced a new regulation in April 2023 aimed at facilitating this transformation.

Key Highlights

- Unprecedented Response:

- Since the implementation of the UGC regulation, colleges seeking autonomous status have witnessed an unprecedented surge in applications, with a total of 590 submissions received.

- This enthusiastic response underscores the perceived value and importance of autonomy in higher education institutions.

- Benefits of Autonomy:

- Promotion of Innovation and Academic Quality:

- Granting autonomy to colleges is crucial for promoting innovation, enhancing academic quality, and fostering institutional excellence.

- Autonomous colleges have the flexibility to tailor their curriculum to align with the evolving needs of students and industries.

- This adaptability enables them to experiment with new teaching methodologies and research initiatives, thus driving the frontiers of knowledge and contributing to societal development.

- Cultivation of Accountability and Responsibility:

- Autonomy fosters a culture of accountability and responsibility among colleges, empowering them to take greater ownership of their academic and administrative decisions.

- This empowerment translates into enhanced institutional efficiency and effectiveness, as colleges become more responsive to the needs and aspirations of their stakeholders.

- Motivation and Excellence:

- Moreover, autonomy cultivates a sense of pride and identity within colleges, motivating faculty and staff to strive for excellence.

- This intrinsic motivation fuels a continuous pursuit of academic and operational excellence, ultimately benefiting the entire higher education ecosystem.

- Impact of Autonomy on College Rankings:

- The National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) of 2023 provides compelling evidence of the positive impact of autonomy on college performance in India.

- In the ‘Colleges Category’, 55 out of the top 100 colleges are identified as autonomous institutions, indicating a correlation between autonomy and academic excellence.

- Among the top 10 colleges listed in the NIRF Rankings of 2023, half of them are autonomous colleges.

- Trend Towards Autonomy:

- The higher education landscape in India is witnessing a notable trend towards the establishment of autonomous colleges, with the current count expected to reach 1,000 across 24 States and Union Territories. States like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana stand out for their substantial presence of autonomous colleges, comprising over 80% of the total count.

- The presence of autonomous colleges in states with varying numbers, including Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Punjab, and West Bengal, underscores a nationwide interest in exploring the potential of autonomy to enhance institutional effectiveness.

- Even in regions with comparatively fewer autonomous institutions, there is a growing realization of the transformative impact autonomy can have on higher education.

- Challenges in Implementing College Autonomy:

- Limitations on Autonomy:

- Despite the advocacy for college autonomy by the University Grants Commission (UGC), certain universities exhibit reluctance to fully relinquish control over colleges.

- This reluctance poses challenges to the effective implementation of autonomy in higher education institutions.

- Imposition of Restrictions:

- Universities often impose limitations on the extent of autonomy granted to colleges.

- Common restrictions include caps on syllabus changes, typically allowing only a fraction, such as 25%-35%, to be altered.

- These constraints inhibit colleges from exercising their autonomy, particularly in areas concerning curriculum development and academic innovation.

- Delays in Recognition:

- Colleges granted autonomy by the UGC encounter delays from universities in recognizing this autonomy.

- These bureaucratic hurdles not only hinder the efficiency of college operations but also undermine the essence of autonomy.

- Colleges may feel constrained by university processes despite their autonomous status.

- Challenges with University Fees and Autonomy:

- Colleges may face arbitrary fees imposed by universities for affiliation purposes.

- This practice not only undermines college autonomy but also raises concerns regarding the transparency and fairness of such fee structures.

- Limitations on Autonomy:

- Call for Effective Implementation:

- State Councils for Higher Education play a pivotal role in ensuring the effective implementation of UGC regulations on autonomy.

- They must oversee and enforce compliance with autonomy guidelines to safeguard the independence of colleges.

- Universities must acknowledge the significance of addressing the concerns of autonomous colleges within the broader context of higher education reform.

- Recognizing the autonomy of colleges is essential for fostering innovation, excellence, and inclusivity in the higher education sector.

- Streamlining Decision-Making:

- To empower autonomous colleges, universities must streamline decision-making processes, fostering greater collaboration and transparency between colleges and universities.

- This ensures that autonomy translates into meaningful empowerment for colleges.

- Universities should cultivate a culture of trust and collaboration with autonomous colleges.

- This entails allowing colleges the freedom to innovate and excel while upholding academic standards, thereby fostering a conducive environment or autonomy to thrive.

- Driving Innovation and Excellence:

- By supporting autonomy, universities can help colleges drive innovation, excellence, and inclusivity in higher education.

- Autonomous colleges should be empowered to experiment with new teaching methodologies, curriculum designs, and research initiatives, contributing to a vibrant and dynamic higher education ecosystem.

- Promotion of Innovation and Academic Quality:

About the University Grants Commission (UGC)

- The University Grants Commission (UGC), known in Hindi as ViśvavidyālayaAnudānaĀyōga, operates under the Department of Higher Education within the Ministry of Education, Government of India.

- Established in accordance with the UGC Act of 1956, the commission is tasked with coordinating, determining, and maintaining standards of higher education throughout India.

- Mandate and Responsibilities:

- The UGC’s primary responsibilities include providing recognition to universities and disbursing funds to recognized universities and colleges across the country.

- It plays a crucial role in ensuring the quality and integrity of higher education institutions in India.

- Organizational Structure:

- Headquartered in New Delhi, the UGC operates through six regional centers located in Pune, Bhopal, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Guwahati, and Bangalore.

- These centers facilitate the commission’s functions and outreach efforts across different regions of India.

- Historical Background:

- The UGC traces its origins back to 1945 when it was initially established to oversee the work of three Central Universities in Aligarh, Banaras, and Delhi.

- Over time, its mandate expanded to cover all universities in India, reflecting the growing importance of higher education in the country.

- In 1949, a recommendation was made to reconstitute the UGC along the lines of the University Grants Committee of the United Kingdom.

- This recommendation, proposed by the University Education Commission of 1948–1949 chaired by S. Radhakrishnan, aimed to enhance the commission’s effectiveness in overseeing Indian university education.

- Statutory Recognition:

- On December 28, 1953, the UGC was officially inaugurated by MaulanaAbulKalam Azad, then Minister of Education, Natural Resources, and Scientific Research.

- It became a statutory organization of the Government of India through an Act of Parliament in 1956, solidifying its role in coordinating, determining, and maintaining standards of teaching, examination, and research in university education nationwide.

- Current Developments and Future Directions:

- Currently, there is a proposal under consideration by the Government of India to replace the UGC with a new regulatory body called the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI).

On global indices measuring democracy

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

2024 marks a significant year for democracy worldwide as half of the world’s population is set to participate in elections, with India being a key focal point due to its large population size and democratic system.

- Recent assessments from prominent institutions like the V-Dem Institute have raised concerns about the state of democracy in India.

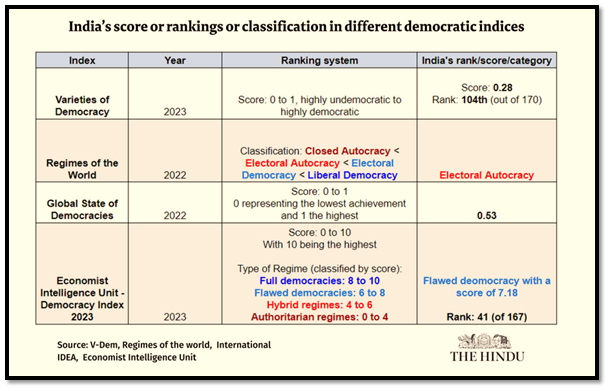

- India has been labeled as “one of the worst autocratisers” by the V-Dem Institute and has faced downgrades in various democracy indices, including being classified as a “partly free” nation by Freedom House and a “flawed democracy” by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Key Highlights

- Government’s Response:

- The Indian government has refuted these assessments and plans to release its own democracy index to counter recent downgrades and criticisms by international groups.

- This move reflects India’s concern over its sovereign ratings and global rankings on indices such as the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators.

- Impact on Sovereign Ratings:

- The criticism and downgrades on democracy indices pose a threat to India’s sovereign ratings and its ranking on international governance indicators, which could have implications for the country’s global standing and investment attractiveness.

- Plans for an Indigenous Index:

- The Central Government announced plans to develop new measures of socio-economic progress, rejecting what it considers “misleading” international parameters.

- It aims to introduce an indigenous index that aligns more closely with India’s socio-political context and aspirations.

- The think tank Observer Research Foundation (ORF), will spearhead the development of India’s proposed index.

- The methodology has undergone peer review by experts and is expected to be unveiled soon.

- Past Attempts at an Indigenous Index:

- India previously considered creating a “world democracy report” and a “global press freedom index” in 2021, following downgrades in reports by the V-Dem Institute and Freedom House.

- However, the details and outcomes of these initiatives remain largely undisclosed.

- Overview of Global Democracy Indices:

- Several organizations produce global democracy indices, each with its own methodology and focus.

- Some prominent examples include the V-Dem Institute, Freedom House, the Economic Intelligence Unit, the Lexical Index, the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, the Worldwide Governance Indicators, and International IDEA’s Global State of Democracies report.

- Types of Data Used:

- Observational Data (OD):

- These include factual information such as voter turnout rates, which are observable and quantifiable.

- In-house Coding:

- Researchers assess country-specific information using academic material, newspapers, and other sources to evaluate democracy indicators.

- Expert Surveys:

- Selected experts from each country provide subjective evaluations based on their knowledge and expertise.

- Representative Surveys:

- A selected group of citizens offer judgments on democracy-related issues, providing insight into public perceptions.

- Approaches to Measurement:

- Fact-based vs. Judgment-based:

- Different indices employ various approaches, some relying solely on factual data, while others incorporate expert judgments or a combination of both.

- Strengths and Drawbacks:

- Each approach has its strengths and limitations.

- While observational data provide objective information, expert judgments offer insights into on-the-ground realities of governance.

- Scholar Svend-Erik Skaaning highlights the importance of establishing a high degree of concept-measure consistency, ensuring that indicators accurately capture the core components of democracy without bias.

- The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights advocates for the use of observational, objective data in democracy assessments to enhance their credibility and acceptance.

- Fact-based vs. Judgment-based:

- Definition of Democracy:

- Democracy is universally recognized as a political system where citizens participate in free and fair elections (electoral democracy).

- Additionally, democracies uphold civic rights and provide protections to citizens, making them liberal societies.

- Dimensions Assessed:

- Indices like V-Dem’s, the Economist Intelligence Unit, and the Bertelsmann Transformation Index evaluate various dimensions of democracy beyond electoral processes.

- They assess factors such as participatory governance, functionality of citizen groups and civil society organizations, deliberative decision-making, and egalitarian distribution of economic and social resources.

- India’s Classification:

- India has faced scrutiny in recent years, being classified as an “electoral autocracy” since 2018 by the V-Dem Institute.

- This classification is attributed to perceived democratic backsliding, crackdowns on civil liberties, and policies fostering religious tensions under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership.

- Limitations of Global Indices:

- Subjectivity and Judgement:

- One major criticism leveled against global indices is their inherent subjectivity, which affects their credibility and precision.

- Despite efforts to use scholarly pools and aggregation models, evaluations still rely on the judgement of researchers and coders rather than objective characteristics.

- Example of Subjective Assessment:

- For instance, V-Dem’s indicator assessing the equality of social groups in the political arena is subjective and open to interpretation, unlike more tangible metrics like the number of political parties in a country.

- Concerns about Bias:

- There are concerns about biases among the experts involved in these assessments.

- Some critics argue that the opinions of intellectuals and professors conducting surveys may be biased against certain political figures or parties.

- Lack of Transparency in Model:

- There are concerns over the transparency of democracy indices’ aggregation models, where experts’ judgments are used to determine which metrics to include and how to weigh each appropriately.

- Questions remain about why certain subindices are chosen and why specific metrics are weighted differently.

- Ideological Discrepancy:

- There are perceived ideological discrepancies in democracy indices due to the amorphous definition of democracy itself.

- For example, Lesotho, which experienced a military coup, may be assigned a higher score than countries like India.

- This raises questions about how economically unequal countries like Brazil can be classified as democratic while India is labeled an electoral autocracy.

- Purpose and Utility of Democracy Indices:

- Despite criticisms, scholars agree that democracy indices capture important dynamics and trends in political regimes.

- They serve as benchmarks for assessing the strengths and weaknesses of democracies over time and across different regions.

- There is no consensus on how democracy should be defined or how its components should be quantified and combined into a single index.

- Each democracy index offers different perspectives and can be used as tools to interrogate various aspects of democracy.

- Subjectivity and Judgement:

- Observational Data (OD):

How are symbols allotted to political parties?

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

Under the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, the Election Commission of India (ECI) recognizes parties as either ‘national’ or ‘state’ parties based on specific criteria.

- These criteria include winning Lok Sabha seats or Legislative Assembly seats, as well as securing a certain percentage of votes in general elections.

Key Highlights

- Importance of Symbols in Voting:

- In India’s vast democracy, where a significant portion of the population may be illiterate, symbols play a crucial role in the voting process.

- Recognized political parties are allotted reserved symbols that are exclusive to them, aiding voters in identifying and supporting their preferred party.

- Allotment of Symbols to Unrecognized Parties:

- For registered but unrecognized political parties, the Election Commission allots one of the free symbols as a common symbol during elections if the party contests in a minimum number of Lok Sabha constituencies or Assembly seats (two Lok Sabha constituencies or 5% of seats to the Assembly of a State).

- These common symbols serve as identifiers for unrecognized parties, allowing voters to distinguish them on the ballot despite not being officially recognized by the Election Commission.

- Rule 10B of Symbols Order:

- Rule 10B of the Symbols Order outlines provisions for the allocation of common symbols to registered but unrecognized parties for general elections.

- These parties are eligible for a common symbol concession for two consecutive elections and must secure at least 1% of votes polled in the previous election to maintain eligibility.

- Case of NTK and VCK:

- In the recent case, NaamTamilarKatchi (NTK) and ViduthalaiChiruthaigalKatchi (VCK) faced issues with symbol allotment.

- Despite NTK securing over 6% of votes in previous elections, they were denied their preferred common symbol due to late application.

- Similarly, VCK was denied a common symbol due to failing to meet the 1% vote threshold, despite having elected representatives.

- Way Forward:

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) has adhered to existing rules in the allocation decisions.

- However, there is a need to reassess these rules to ensure fairness and inclusivity in the electoral process.

- Consideration of Past Performance:

- One proposal is to amend the rules to grant registered unrecognised parties eligibility for a common symbol if they have secured at least 1% of votes in a previous election or have elected representatives in the Lok Sabha or State Assembly.

- Such amendments would acknowledge the electoral performance and representation of unrecognised parties, providing them with equitable opportunities in the electoral process.

- This would strengthen the democratic framework and promote fairness in elections.

What is the criteria to be recognized as a state party or a national party in India?

- State Party Criteria:

- Securing Votes in State Elections:

- The party must secure at least 6% of the valid votes polled in the state at a general election to the legislative assembly of the state concerned.

- Additionally, the party must win at least 2 seats in the legislative assembly of that state at such a general election.

- OR, the party must secure 6% of the total valid votes polled in the state at a general election to the Lok Sabha from the state concerned.

- Additionally, the party must win at least 1 seat in the Lok Sabha from the state at such a general election.

- Winning Seats in State Elections:

- The party must win at least 3% of the total number of seats in the legislative assembly at a general election to the legislative assembly of the state concerned, or at least 3 seats in the assembly, whichever is more.

- OR, the party must win 1 seat in the Lok Sabha for every 25 seats or any fraction thereof allotted to the state at a general election to the Lok Sabha.

- OR, the party must secure 8% of the total valid votes polled in the state at a General Election to the Lok Sabha from the state or to the state legislative assembly.

- National Party Criteria:

- The party must secure at least 6% of the total valid votes polled in each of four or more states at a general election to the Lok Sabha or to the legislative assembly.

- Additionally, the party must win at least four seats in the Lok Sabha from any state or states.

- OR, the party must win at least 2% of the total number of seats in the Lok Sabha at a general election, and these candidates must be elected from three states.

- OR, the party must be recognized as a state party in four states.

- Securing Votes in State Elections: