CURRENT AFFAIRS – 26/04/2024

CURRENT AFFAIRS – 26/04/2024

Can Govt redistribute privately owned property?

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Indian Express

The Supreme Court of India commenced hearings on April 24 regarding a case related to wealth distribution.

- This case pertains to the government’s authority to acquire and redistribute privately owned properties if they are deemed essential for the common good, as stipulated in Article 39(b) of the Constitution.

Key Highlights

- Relevance of Article 39(b):

- Article 39(b) is part of Part IV of the Constitution, known as “Directive Principles of State Policy” (DPSP).

- It mandates the state to formulate policies ensuring the equitable distribution of material resources for the collective welfare.

- Interpretation of Article 39(b):

- The apex court has previously addressed the interpretation of Article 39(b), notably in the 1977 case of State of Karnataka v Shri Ranganatha Reddy.

- In this landmark case, a seven-judge Bench, with a 4:3 majority, ruled that privately owned resources did not qualify as “material resources of the community” under Article 39(b).

- However, Justice Krishna Iyer’s minority opinion in the same case has had a lasting impact.

- He argued that privately owned resources should indeed be considered as part of the community’s material resources.

- According to him, any valuable or useful asset in the material world contributes to the community’s resources, including those owned by individuals.

- Excluding private ownership from Article 39(b) undermines its intended goal of socialist redistribution.

- Significance of Justice Iyer’s Perspective:

- Justice Iyer’s perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of individual and communal resources, advocating for a broader interpretation of Article 39(b).

- His viewpoint suggests that the exclusion of privately owned resources undermines the objective of equitable redistribution, aligning with socialist principles.

- Implications of the Case:

- The ongoing case before the Supreme Court will likely address the scope of government intervention in private property rights for the collective welfare, weighing interpretations of Article 39(b) and the precedent set by previous rulings, including Justice Iyer’s influential minority opinion.

- The interpretation of Article 39(b) by Justice Krishna Iyer, which advocated for the inclusion of privately owned resources as community assets, received validation from the Supreme Court in subsequent cases.

- Sanjeev Coke Manufacturing Company v Bharat Coking Coal (1983):

- In this case, a five-judge Bench upheld legislation that nationalized coal mines and associated coke oven plants, drawing upon Justice Iyer’s interpretation of Article 39(b).

- The court concluded that the provision extends to the transformation of wealth from private to public ownership, not solely limited to pre-existing public assets.

- Concurring Opinion in Mafatlal Industries Ltd v Union of India (1996):

- Further bolstering Justice Iyer’s interpretation, Justice Paripoornan, in the Mafatlal Industries case, endorsed the broad understanding of Article 39(b) as proposed by Justice Iyer.

- He emphasized that “material resources” encompass not only natural or physical resources but also movable and immovable properties, both private and public.

- This expansive interpretation underscores the comprehensive nature of resources crucial for meeting societal needs.

- Influence on Subsequent Jurisprudence:

- The reliance on Justice Iyer’s interpretation in subsequent cases indicates its enduring influence on judicial reasoning concerning property rights and the common good.

- These decisions underscore a departure from a strict dichotomy between private and public ownership, recognizing the interconnectedness of resources for the collective welfare.

- Implications for Property Rights and Social Policy:

- The affirmation of Justice Iyer’s perspective has significant implications for property rights and social policy in India.

- It suggests a legal framework that enables the state to intervene in private ownership for the greater public good, aligning with principles of equitable distribution and social welfare enshrined in Article 39(b) of the Constitution.

- Background of the Cessed Properties Dispute:

- The current case before the Supreme Court (SC) stems from a challenge to the 1986 amendment to the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Act, 1976 (MHADA) by owners of “cessed” properties in Mumbai.

- Purpose of MHADA:

- MHADA, enacted in 1976, aimed to address the issue of old, deteriorating buildings in Mumbai housing poor tenants, which posed safety hazards.

- It introduced a cess on the occupants of these buildings, with funds directed to the Mumbai Building Repair and Reconstruction Board (MBRRB) for repair and restoration projects.

- 1986 Amendment and Chapter VIII-A:

- In 1986, an amendment to MHADA, invoking Article 39(b), introduced Section 1A to facilitate the acquisition of lands and buildings for transfer to “needy persons” and occupants.

- Additionally, Chapter VIII-A was added, allowing the state government to acquire cessed buildings and their land if 70% of the occupants requested such action.

- Legal Challenge and High Court Decision:

- The Property Owners’ Association in Mumbai challenged Chapter VIII-A of MHADA in the Bombay High Court, arguing it violated the property owners’ Right to Equality under Article 14 of the Constitution.

- The High Court, citing Article 31C (“Saving of laws giving effect to certain directive principles”), held that laws enacted to fulfill Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) could not be contested for violating the right to equality.

- Appeal to the Supreme Court:

- The Association appealed the High Court decision to the Supreme Court in December 1992.

- The central issue before the SC became whether privately owned resources, including cessed buildings, fell under the purview of “material resources of the community” as per Article 39(b) of the Constitution.

- Referral to Larger Bench:

- In March 2001, a five-judge Bench heard the case and referred it to a larger Bench, citing the need for reconsideration in light of the views expressed in the Sanjeev Coke Manufacturing case.

- Reconsideration by Seven-Judge Bench:

- In February 2002, a seven-judge Bench acknowledged Justice Iyer’s interpretation but expressed skepticism, stating reluctance to broadly define “material resources of the community” to include privately owned assets.

- The challenge to Chapter VIII-A of MHADA was then referred to a nine-judge Bench, which is currently hearing the case.

About the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP)

- The Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) are guidelines and principles laid down in Part IV of the Indian Constitution. Unlike Fundamental Rights (Part III), which are justiciable and enforceable by courts, DPSPs are non-justiciable and cannot be enforced by the courts.

- However, they serve as important principles for the governance of the country and are considered fundamental in the governance of the state.

- Objectives:

- Social Justice: To promote social, economic, and political justice and to create a just and equitable society.

- Welfare State: To establish a welfare state where the state takes responsibility for the well-being of its citizens and ensures social and economic equality.

- Gandhian Principles: To promote the principles of Gandhian socialism, including decentralization, village self-governance, and economic equality.

- Features:

- Non-Justiciable: Unlike Fundamental Rights, DPSPs are not legally enforceable by the courts. However, they serve as guiding principles for the government in policy-making and legislation.

- Comprehensive: DPSPs cover a wide range of areas, including social justice, economic development, international relations, governance, and cultural heritage.

- Positive Obligations: DPSPs impose positive obligations on the state to take affirmative action to promote the welfare of the people and achieve the objectives laid down in the Constitution.

- Categories of DPSPs:

- Socialistic Principles: These include principles related to the distribution of wealth, resources, and means of production to ensure social and economic justice.

- Gandhian Principles: These principles emphasize decentralization, village self-governance, and promotion of cottage industries to achieve economic equality.

- Liberal Principles: These principles focus on promoting individual liberties, rights of minorities, and equality before law.

What is Art 244(A), the constitutional promise of autonomy for Assam Tribal Area?

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Indian Express

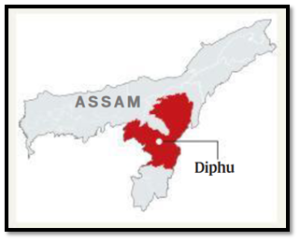

DiphuLok Sabha constituency, located in Assam, is characterized by its tribal-majority demographic and its historical emphasis on the implementation of Article 244(A) of the Constitution.

- This provision holds significant importance in the constituency’s electoral landscape, with candidates from all parties pledging its implementation as a primary election promise for decades.

Key Highlights

- Significance of Article 244(A)

- Article 244(A) of the Constitution, introduced by The Constitution (Twenty-second Amendment) Act, 1969, empowers Parliament to establish an autonomous state within Assam, encompassing specific tribal areas, including KarbiAnglong.

- This provision aims to provide these areas with greater autonomy by granting them their own Legislature or Council of Ministers, or both.

- Location and Social Profile of Diphu

- Diphu, the most sparsely populated among Assam’s 14 Lok Sabha constituencies, is reserved for Scheduled Tribes (STs).

- It comprises six legislative Assembly segments spread across three tribal-majority hill districts:

- KarbiAnglong, West KarbiAnglong, and Dima Hasao.

- These areas are administered under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, which delineates provisions for the administration of tribal areas in several northeastern states.

- Autonomous Councils and Representation

- The region is governed by two autonomous councils:

- the KarbiAnglong Autonomous Council (KAAC) and the North Cachar Hills Autonomous Council.

- Despite the diverse ethnic composition of its electorate, the DiphuLok Sabha seat has predominantly been represented by members of the Karbi community since 1977.

- Presently, all Assembly segments within the constituency are under the control of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

- Comparison with Sixth Schedule

- While the existing Sixth Schedule provisions entail elected representatives for decentralized governance, these councils have limited legislative powers and lack control over law and order, as well as limited financial autonomy.

- Article 244(A) presents a more comprehensive approach to autonomy, surpassing the provisions of the Sixth Schedule and aiming to provide greater self-governance to tribal areas like KarbiAnglong.

- Origins of Autonomy Demand:

- The demand for autonomy in Assam’s hill areas dates back to the 1950s when movements emerged seeking a separate hill state.

- While Meghalaya was carved out as a full-fledged state in 1972, leaders of the KarbiAnglong region chose to remain with Assam due to assurances provided by Article 244(A) of the Constitution.

- The Autonomous State Demand Committee (ASDC), established as a mass organization advocating for autonomy, signed a Memorandum of Settlement in 1995 to enhance the powers of the two autonomous councils in the region.

- Despite these efforts, autonomy remained elusive, prompting ASDC’s continued activism.

- Armed Insurgency and Peace Accords:

- Frustration over the lack of progress towards autonomy led to armed insurgency, with demands for the implementation of Article 244(A).

- The governments in Delhi and Guwahati have engaged in peace talks with various militant groups, including those in the Karbi and Dimasa regions.

- Recent Developments:

- In 2021, peace settlements were reached with five militant groups in KarbiAnglong, offering greater autonomy and a special development package.

- Similarly, an agreement was signed with the Dimasa National Liberation Army, reflecting ongoing efforts to address autonomy demands through dialogue and negotiation.

- The region is governed by two autonomous councils:

About the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution

- The Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution pertains to the administration of tribal areas in the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

- Autonomous District Councils (ADCs):

- The Sixth Schedule establishes Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) within the tribal areas.

- These councils have legislative, executive, and financial powers to govern the areas under their jurisdiction.

- The ADCs are empowered to make laws on various subjects, including land, forests, agriculture, and local governance.

- Composition of ADCs:

- The composition of ADCs typically includes elected members from tribal communities, as well as nominated members.

- The number of seats and the method of election are determined by the respective state governments in consultation with tribal representatives.

- Powers and Functions:

- Legislative Functions

- The District Councils and Regional Councils have the power to enact laws on a number of subjects like land, forests, canal water, shifting agriculture, village administration, inheritance, marriage and divorce, social customs, etc.

- However, all such laws require the approval of the state Governor before taking effect.

- Executive Functions

- The Councils have the authority to develop, build, and manage primary schools, dispensaries, markets, cattle ponds, fisheries, roads, and waterways in their districts.

- They also have the power to determine the language and medium of instruction in primary schools.

- Judicial Functions

- The Councils can establish Village and District Council Courts to administer justice, but these courts cannot handle cases involving offenses punishable by death or imprisonment of 5 years or more.

- Financial Powers

- The Councils can prepare their own budgets and have the power to levy and collect certain taxes like land revenue, taxes on professions, trades, animals, vehicles, goods brought for sale in markets, and tolls on ferries.

- They can also grant licenses or leases for the extraction of minerals within their jurisdiction.

- Governor’s Role:

- The Governor of the state exercises certain powers regarding the administration of tribal areas under the Sixth Schedule.

- The Governor has the authority to issue regulations for the peace, progress, and good governance of the autonomous districts.

- Legislative Functions

RBI’s draft rules for payment aggregators

(General Studies- Paper II and III)

Source : The Hindu

In June 2022, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced its intention to regulate offline payment aggregators (PAs) facilitating proximity or face-to-face transactions.

- This move aims to extend existing guidelines, which primarily focus on online transactions, to cover activities in offline spaces.

Key Highlights

- Scope of Regulation:

- Payment aggregators act as intermediaries between customers and merchants, streamlining the payment process for merchants who would otherwise need to develop their own payment integration systems.

- The proposed regulations seek to bring offline PA activities in line with those conducted online, noting the similarity in nature between the two.

- Objectives:

- The RBI aims to establish synergy in regulation across online and offline PA activities, with a focus on standardizing data collection and storage practices.

- By doing so, it aims to enhance transparency and accountability within the payment ecosystem.

- Key Components of the Proposed Norms:

- Expansion to Offline Spaces:

- The regulations will extend existing guidelines to cover transactions conducted in proximity or face-to-face settings, ensuring that offline PA activities are subject to similar scrutiny as their online counterparts.

- Enhanced KYC and Due Diligence:

- The proposed norms include provisions for strengthening Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures and due diligence processes for onboarding merchants.

- This aims to mitigate risks associated with illicit activities, as evidenced by the Paytm Payments Bank (PPBL) crisis, which revealed lapses in KYC adherence.

- Escrow Account Operations:

- Additionally, the regulations propose measures to regulate operations in Escrow accounts, enhancing the safety and integrity of transactions facilitated by PAs.

- This is particularly relevant in light of instances where funds were misused, such as in the PPBL case where money generated from illegal activities was channeled through bank accounts maintained by the entity.

- Compulsory Registration with RBI:

- Registration with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is being made compulsory for non-bank payment aggregators (PAs), particularly focusing on offline extensions.

- Banks offering physical PA services as part of their regular banking operations are exempt from separate authorization, but they must comply with revised instructions within three months of issuance.

- Registration Process for Non-Banking Entities:

- Non-banking entities providing PA services at point of sale (PoS), offline, must inform the RBI within 60 days of the circular’s issuance about their intent to seek authorization.

- These entities can continue operations while their applications are under review.

- For non-banking entities providing PA services online, both authorized and pending applicants must seek approval for their existing offline PA activities from the Department of Payment and Settlement Systems (DPSS) and the regulator within 60 days of mandated directions.

- This requirement also applies to authorized non-banking entities planning to enter the online and/or offline PA space in the future.

- Adherence to Guidelines and Compliance:

- Entities currently engaged in PoS activities must ensure compliance with guidelines on merchant onboarding, customer grievance redressal, dispute management, technology recommendations, security, fraud prevention, and risk management within three months.

- For entities requiring fresh registration, continued adherence to existing guidelines from 2020 governing e-commerce transactions will be viewed positively during the application process.

- Provisions for Sustainability:

- RBI proposes a minimum net worth requirement of ₹15 crore for non-banking entities providing proximity/face-to-face transaction services, which will increase to ₹25 crore by March 31, 2028.

- New applicants must also meet this net worth requirement, with the difference being that the ₹25 crore requirement applies at the end of three financial years when authorization is granted.

- Existing offline operators unable to comply with the approval-seeking timeframe must wind up their operations by July 31, 2025.

- Banks failing to produce evidence of their application seeking authorization will be directed to close all accounts by the end of October next year.

- KYC Requirements for Merchants:

- The proposed regulations aim to ensure that onboarded merchants only collect and settle funds for services offered on their platforms.

- Merchants are categorized into small and medium categories based on their annual turnover and GST registration status.

- Small merchants, with an annual turnover of less than ₹5 lakh and not registered under GST, require ‘contact point verification’ by PAs to establish their existence and verify bank accounts.

- Medium merchants, with an annual turnover of less than ₹40 lakhs and not registered under GST, also undergo contact point verification.

- PAs must verify official documents of the proprietor, beneficial owner, or attorney holder, and of the business.

- Ongoing Compliance and Risk-Based Payments:

- PAs must ensure that transactions by merchants align with their business profile and assign risk-based payments to them.

- Merchants’ due diligence levels may be adjusted based on transaction patterns, following existing norms for risk management and compliance.

- Storage of Card Data:

- The regulations prohibit entities, other than card issuers and networks, from storing data for proximity/face-to-face payments starting from August 1, 2025.

- Entities can retain limited data, such as the last four digits of the card number and the issuer’s name, for transaction tracking and reconciliation purposes.

- Card networks are responsible for ensuring compliance with these storage regulations.

- Expansion to Offline Spaces:

What is a bank and non-bank entity in India?

In India, both banks and non-bank entities play important roles in the financial system, but they have distinct functions and regulatory frameworks.

- Banks:

- Banks are financial institutions that are licensed to accept deposits from the public and provide various banking services, including lending, investment, and payment services.

- In India, banks are regulated and supervised by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central banking authority in the country.

- Banks can be classified into several categories based on their ownership, structure, and functions:

- Scheduled Commercial Banks: These are banks that are included in the Second Schedule of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. Scheduled commercial banks can further be categorized into public sector banks, private sector banks, and foreign banks operating in India.

- Cooperative Banks: These are banks that are owned and operated by their members, who are typically individuals or small businesses within a specific geographic area. Cooperative banks in India are regulated by the RBI as well as by state-level cooperative societies.

- Regional Rural Banks (RRBs): RRBs are banks established with the objective of providing credit and other banking services to rural areas and agricultural communities. They are jointly owned by the central government, the concerned state government, and a sponsor bank.

- Non-Bank Entities:

- Non-bank entities, also known as non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs) or financial intermediaries, are institutions that provide financial services but do not hold a banking license or accept deposits from the public.

- These entities complement the services offered by banks and cater to specific financial needs.

- Non-bank entities in India are regulated by various regulatory bodies, including the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), and Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI).

- Examples of non-bank entities in India include:

- Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs): NBFCs are financial institutions that provide a wide range of banking services, such as loans and advances, asset financing, and investment services, but do not hold a banking license. They play a crucial role in providing credit to sectors that may not have access to traditional banking services.

- Insurance Companies: Insurance companies provide various types of insurance products, including life insurance, health insurance, and general insurance, to individuals and businesses. They are regulated by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI).

- Mutual Funds: Mutual funds pool money from investors and invest in a diversified portfolio of securities, such as stocks, bonds, and money market instruments. They offer investors the opportunity to participate in the financial markets with relatively low investment amounts and professional management.

- Housing Finance Companies (HFCs): HFCs provide financing for the purchase, construction, and renovation of residential properties. They specialize in mortgage loans and play a key role in the housing finance sector.

- Payment Banks: Payment banks are a specialized category of banks that focus on providing payment services, remittance facilities, and other banking services, but do not engage in lending activities. They are regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and cater primarily to underserved segments of the population.

Why does the Centre want to modify the 2G spectrum verdict?

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

More than a decade after the Supreme Court’s cancellation of 122 telecom licenses in the landmark 2G spectrum scam judgment, the Union government has proposed a change in the allocation process.

- The 2G spectrum scam involved the alleged irregular allocation of 2G licenses by the then Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2008, resulting in a significant loss to the exchequer.

Key Highlights

- Proposal for Administrative Allocation:

- The government has moved an application seeking administrative allocation of a “certain class” of spectrum instead of competitive auctions.

- Administrative allocation would grant the government authority to determine the selection procedure for operators, bypassing the auction process mandated by the Supreme Court.

- Supreme Court’s Stance on Allocation of Natural Resources:

- In its 2012 judgment, the Supreme Court canceled the licenses and cautioned against the misuse of FCFS (first-come-first-serve) basis for allocating scarce natural resources.

- The Court endorsed competitive auctions as the preferred method for allocation, stressing the importance of wide publicity and non-discriminatory participation to ensure transparency and fairness.

- Centre’s Plea for Administrative Allocation:

- The Centre argues that spectrum assignment is essential not only for commercial telecom services but also for sovereign and public interest functions like security, safety, and disaster preparedness.

- Certain categories of spectrum usage, such as captive, backhaul, or sporadic use, may not be economically or technically suited for auctions.

- Administrative allocation is deemed necessary when demand is lower than supply or for specialized uses like space communication, where spectrum sharing among multiple players is more efficient than exclusive assignment.

- Rationale for the Plea:

- Since the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling, administrative assignment of non-commercial spectrum has been provisional, pending final government decisions on pricing and policy.

- The government now seeks to establish a definitive spectrum assignment framework, including methods other than auctions, to serve the common good more effectively.

- The plea requests appropriate clarifications that the government may consider administrative spectrum assignment through due process if it serves governmental functions or public interest, or if auctions are not preferred due to technical or economic reasons.

- The government cites observations from a Constitution Bench regarding a Presidential reference made concerning the 2012 verdict.

- While the auction method was recommended as preferable for the disposal of natural resources, the Bench noted that situations requiring methods other than auctions were conceivable and desirable.

- However, it emphasized that spectrum allocation should strictly adhere to auction methods as mandated by the 2G case verdict, cautioning against deviations from this principle.

- The Telecommunications Act, 2023: Empowering Spectrum Assignment

- The Telecommunications Act, 2023, passed by the Parliament last year, introduces provisions enabling the government to assign spectrum for telecommunication purposes through administrative processes other than auction.

- Entities Listed in the First Schedule:

- Entities listed in the First Schedule of the Act are eligible for spectrum assignment through administrative processes.

- These include entities engaged in national security, defence, and law enforcement.

- Additionally, Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellites (GMPCS) providers such as Space X and Bharti Airtel-backed OneWeb are also included in this category.

- The government is empowered to assign spectrum to these entities without resorting to auction methods.

- This allows for more flexibility in spectrum allocation, especially for critical functions related to national security and satellite communication.

- Secondary Assignees:

- The Act also permits the government to assign part of a spectrum that has already been allocated to one or more primary entities.

- These additional entities, known as secondary assignees, can benefit from spectrum allocation for specific purposes outlined in the legislation.

- Termination of Assignments:

- Furthermore, the Act grants the government the authority to terminate spectrum assignments in cases where the spectrum or a portion of it remains underutilized for insufficient reasons.

- This provision ensures efficient use of spectrum resources and encourages entities to maximize their utilization.

- Other Key Highlights of the Telecommunication Act:

- Assignment of Spectrum:

- The Act mandates the assignment of spectrum through an auction process for efficient use and to prevent interference between operators.

- It also allows for administrative assignment for specific purposes like national disaster management and public broadcasting services

- Powers of Interception and Search:

- The Act grants the government the power to intercept and detain messages, subject to legal sanction and proportionality, to ensure national security.

- However, misuse of this power could infringe on fundamental rights.

- Authorization Regime:

- Entities providing telecommunication services, operating networks, or possessing radio equipment must obtain authorization from the central government, replacing the previous licensing regime.

- Expanded Scope:

- The definition of “telecommunication services” is broad, covering any service involving transmission, emission or reception of messages by wire, radio, optical or other electromagnetic systems.

- Regulatory Powers:

- The government is empowered to take possession of services/networks and direct interception or disclosure of messages in the event of a public emergency or in the interest of public safety.

- User Verification:

- Authorized entities are required to verify individuals receiving telecommunication services, aiming to reduce spam calls and messages.

- Digital Bharat Nidhi:

- The Act establishes a fund called the Digital Bharat Nidhi to replace the existing Universal Service Obligation Fund, aimed at promoting universal access to telecommunication services.

- Offences and Penalties:

- The Act prescribes criminal penalties, including imprisonment, for offences like providing services without authorisation or intercepting messages.

- Civil penalties can also be levied based on revenue loss caused to the government.

- Assignment of Spectrum:

New test to diagnose special learning disabilities in adults

(General Studies- Paper II)

Source : The Hindu

The Union government of India is set to introduce a new test for diagnosing specific learning disabilities (SLDs) in adults by the end of the year.

- This initiative aims to address a significant gap in the accessibility of disability certificates under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016.

Key Highlights

- Background:

- The absence of diagnostic methods for testing SLDs in adults has been highlighted in a writ petition before the Supreme Court.

- This absence has hindered adults from obtaining disability certificates necessary for availing benefits under the RPwD Act, such as reservation in government institutions and jobs.

- Certification Requirements and Changes:

- Previously, certification for SLDs required clinical assessment, IQ assessment, and SLD assessment, typically initiated at the age of 8 and repeated at later stages of education.

- However, the introduction of SLDs in the list of disabilities in 2016 inadvertently excluded adults since the disorder necessitates early diagnosis.

- Development of New Test:

- The National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (NIEPID) in Secunderabad, Telangana, is tasked with designing the new test.

- Senior officials in the Social Justice Ministry have confirmed that the test is currently under development and is expected to undergo validation against global standards before its phased rollout by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities.

About the Right to Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act

- The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act, 2016 is a landmark legislation in India that aims to uphold the dignity of every Person with Disability (PwD) and ensure their full participation and inclusion in society.

- It replaces the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995, and fulfills India’s obligations to the United National Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

- Key features of the RPWD Act, 2016 include:

- Definition of Disability:

- The Act defines disability based on an evolving and dynamic concept, covering 21 types of disabilities, including physical, mental, intellectual, and sensory impairments.

- Accessibility:

- The Act emphasizes the need for accessibility in public buildings, transportation, and information and communication technology to ensure equal participation of PwDs in society.

- Education:

- The Act mandates free and compulsory education for children with benchmark disabilities between the ages of 6 and 18 years, and inclusive education in government-funded and recognized institutions.

- Employment:

- The Act provides for reservation in government jobs and educational institutions, and additional benefits for persons with benchmark disabilities and those with high support needs.

- Guardianship:

- The Act introduces joint decision-making between the guardian and the person with disabilities in matters of guardianship.

- Advisory Bodies:

- The Act establishes Central and State Advisory Boards on Disability to serve as apex policy-making bodies at the national and state levels.

- Monitoring and Grievance Redressal:

- The Act strengthens the offices of the Chief Commissioner of Persons with Disabilities and State Commissioners of Disabilities, which will act as regulatory bodies and grievance redressal agencies, and monitor the implementation of the Act.

- Penalties:

- The Act provides for penalties for offenses committed against persons with disabilities and violation of the provisions of the new law.

- Special Courts:

- The Act designates special courts in each district to handle cases concerning violation of the rights of PwDs.

- Definition of Disability: